Governance

Description

What Is Governance?

The system by which organizations are directed and controlled. [Cadbury 1992]

To talk about governing digital or IT capabilities, we must talk about governance in general. Governance is a challenging and often misunderstood concept. First and foremost, it must be distinguished from “management”. This is not always easy but remains essential. The ISACA COBIT framework, across its various versions, has made a clear distinction between governance and management, which encompass different types of activities, organizational structures, and purposes. In most enterprises, governance is the responsibility of the Board of Directors under the leadership of the chairperson while management is the responsibility of the executive management under the leadership of the CEO.

A Governance Example

Here is a simple explanation of governance:

Suppose you own a small retail store. For years, you were the primary operator. You might have hired an occasional cashier, but that person had limited authority; they had the keys to the store and cash register, but not the safe combination, nor was their name on the bank account. They did not talk to your suppliers. They received an hourly wage, and you gave them direct and ongoing supervision.[1] In this case, you were a manager. Governance was not part of the relationship.

Now, you wish to go on an extended vacation – perhaps a cruise around the world, or a trek in the Himalayas. You need someone who can count the cash and deposit it, and place orders with and pay your suppliers. You need to hire a professional manager.

They will likely draw a salary, perhaps some percentage of your proceeds, and you will not supervise them in detail as you did the cashier. Instead, you will set overall guidance and expectations for the results they produce. How do you do this? And perhaps even more importantly, how do you trust this person?

Now, you need governance.

As we see in the above quote, one of the most firmly reinforced concepts in the COBIT guidance (more on this and ISACA in the next section) is the need to distinguish governance from management. Governance is by definition a Board-level concern. Management is the CEO’s concern. In this distinction, we can still see the shop owner and their delegate.

Theory of Governance

In political science and economics, the need for governance is seen as an example of the principal-agent problem [Eisenhardt 1989]. Our shopkeeper example illustrates this. The hired manager is the “agent”, acting on behalf of the shop owner, who is the “principal”.

In principal-agent theory, the agent may have different interests than the principal. The agent also has much more information (think of the manager running the shop day-to-day, versus the owner off climbing mountains). The agent is in a position to do economic harm to the principal; to shirk duty, to steal, to take kickbacks from suppliers. Mitigating such conflicts of interest is a part of governance.

In larger organizations (such as you are now), it is not just a simple matter of one clear owner vesting power in one clear agent. The corporation may be publicly owned, or in the case of a non-profit, it may be seeking to represent a diffuse set of interests (e.g., environmental issues). In such cases, a group of individuals (directors) is formed, often termed a “Board”, with ultimate authority to speak for the organization.

The principal-agent problem can be seen at a smaller scale within the organization. Any manager encounters it to some degree, in specifying activities or outcomes for subordinates. But this does not mean that the manager is doing “governance”, as governance is by definition an organization-level concern.

The fundamental purpose of a Board of Directors and similar bodies is to take the side of the principal. This is easier said than done; Boards can become overly close to an organization’s senior management – the senior managers are real people, while the “principal” may be an amorphous, distant body of shareholders and/or stakeholders.

Because governance is the principal’s concern, and because the directors represent the principal, governance, including IT governance, is a Board-level concern.

There are various principles of corporate governance we will not go into here, such as shareholder rights, stakeholder interests, transparency, and so forth. However, as we turn to our focus on digital and IT-related governance, there are a few final insights from the principal-agent theory that are helpful to understanding governance. Consider: “the heart of principal-agent theory is the trade-off between (a) the cost of measuring behavior and (b) the cost of measuring outcomes and transferring risk to the agent” [Eisenhardt 1989].

What does this mean? Suppose the shopkeeper tells the manager, “I will pay you a salary of $50,000 while I am gone, assuming you can show me you have faithfully executed your daily duties.”?

The daily duties are specified in a number of checklists, and the manager is expected to fill these out daily and weekly, and for certain tasks, provide evidence they were performed (e.g., bank deposit slips, checks written to pay bills, photos of cleaning performed, etc.). That is a behavior-driven approach to governance. The manager need not worry if business falls off; they will get their money. The owner has a higher level of uncertainty; the manager might falsify records, or engage in poor customer service so that business is driven away. A fundamental conflict of interest is present; the owner wants their business sustained, while the manager just wants to put in the minimum effort to collect the $50,000. When agent responsibilities can be well specified in this manner, it is said they are highly programmable.

Now, consider the alternative. Instead of this very scripted set of expectations, the shopkeeper might tell the manager, “I will pay you 50% of the shop’s gross earnings, whatever they may be. I will leave you to follow my processes however you see fit. I expect no customer or vendor complaints when I get back.”

In this case, the manager’s behavior is more aligned with the owner’s goals. If they serve customers well, they will likely earn more. There are any number of hard-to-specify behaviors (less programmable) that might be highly beneficial.

For example, suppose the store manager learns of an upcoming street festival, a new one that the owner did not know of or plan for. If the agent is managed in terms of their behavior, they may do nothing – it is just extra work. If they are measured in terms of their outcomes, however, they may well make the extra effort to order merchandise desirable to the street fair participants, and perhaps hire a temporary cashier to staff an outdoor booth, as this will boost store revenue and therefore their pay.

(Note that we have considered similar themes in our discussion of Agile and contract management, in terms of risk sharing.)

In general, it may seem that an outcome-based relationship would always be preferable. There is, however, an important downside. It transfers risk to the agent (e.g., the manager). And because the agent is assuming more risk, they will (in a fair market) demand more compensation. The owner may find themselves paying $60,000 for the manager’s services, for the same level of sales, because the manager also had to “price in” the possibility of poor sales and the risk that they would only make $35,000.

Finally, there is a way to align interests around outcomes without going fully to performance-based pay. If the manager for cultural reasons sees their interests as aligned, this may mitigate the principal-agent problem. In our example, suppose the store is in a small, tight-knit community with a strong sense of civic pride and familial ties.

Even if the manager is being managed in terms of their behavior, their cultural ties to the community or clan may lead them to see their interests as well aligned with those of the principal. As noted in Eisenhardt 1989: “Clan control implies goal congruence between people and, therefore, the reduced need to monitor behavior or outcomes. Motivation issues disappear.” We have discussed this kind of motivation in Coordination and Process, especially in our discussion of control culture and insights drawn from the military.

COSO and Control

Internal control is a process, effected by an entity’s Board of Directors, management, and other personnel, designed to provide reasonable assurance regarding the achievement of objectives relating to operations, reporting, and compliance. [COSO 2017]

Internal Control – Integrated Framework

An important discussion of governance is found in the statements of COSO on the general topic of “control”.

Control is a term with broader and narrower meanings in the context of governance. In the area of risk management, “controls” are specific approaches to mitigating risk. However, “control” is also used by COSO in a more general sense to clarify governance.

According to COSO, control activities are: “the actions established through policies and procedures that help ensure that management’s directives to mitigate risks to the achievement of objectives are carried out. Control activities are performed at all levels of the entity, at various stages within business processes, and over the technology environment. They may be preventive or detective in nature and may encompass a range of manual and automated activities such as authorizations and approvals, verifications, reconciliations, and business performance reviews… Ongoing evaluations, built into business processes at different levels of the entity, provide timely information. Separate evaluations, conducted periodically, will vary in scope and frequency depending on assessment of risks, effectiveness of ongoing evaluations, and other management considerations. Findings are evaluated against criteria established by regulators, recognized standard-setting bodies or management, and the Board of Directors, and deficiencies are communicated to management and the Board of Directors as appropriate” [COSO2017].

Analyzing Governance

Governance Context

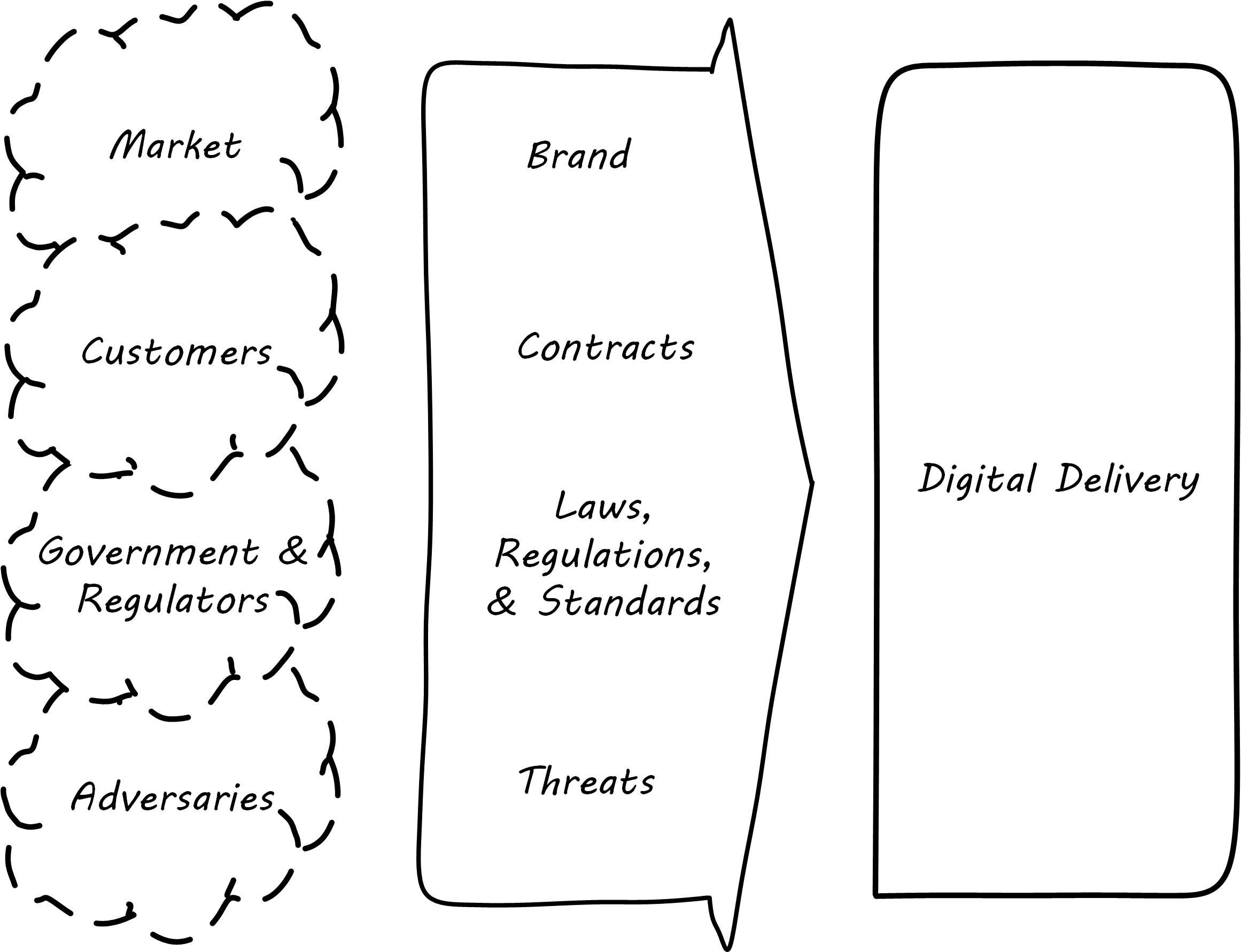

Governance is also a practical concern for you because, at your scale, you have a complex set of environmental forces to cope with; see Governance in Context. You started with a focus on the customer, and the market they represented. Sooner or later, you encountered regulators and adversaries: competitors and cybercriminals.

These external parties intersect with your reality via various channels:

-

Your brand, which represents a sort of general promise to the market; see Sussna 2015

-

Contracts, which represent more specific promises to suppliers and customers

-

Laws, regulations, and standards, which can be seen as promises you must make and keep in order to function in civil society, or in order to obtain certain contracts

-

Threats, which may be of various kinds:

-

Legal

-

Operational

-

Intentional

-

Unintentional

-

Illegal

-

Environmental

-

We will return to the role of external forces in our discussion of assurance. For now, we will turn to how digital governance, within an overall system of digital delivery, reflects our emergence model.

Governance and the Emergence Model

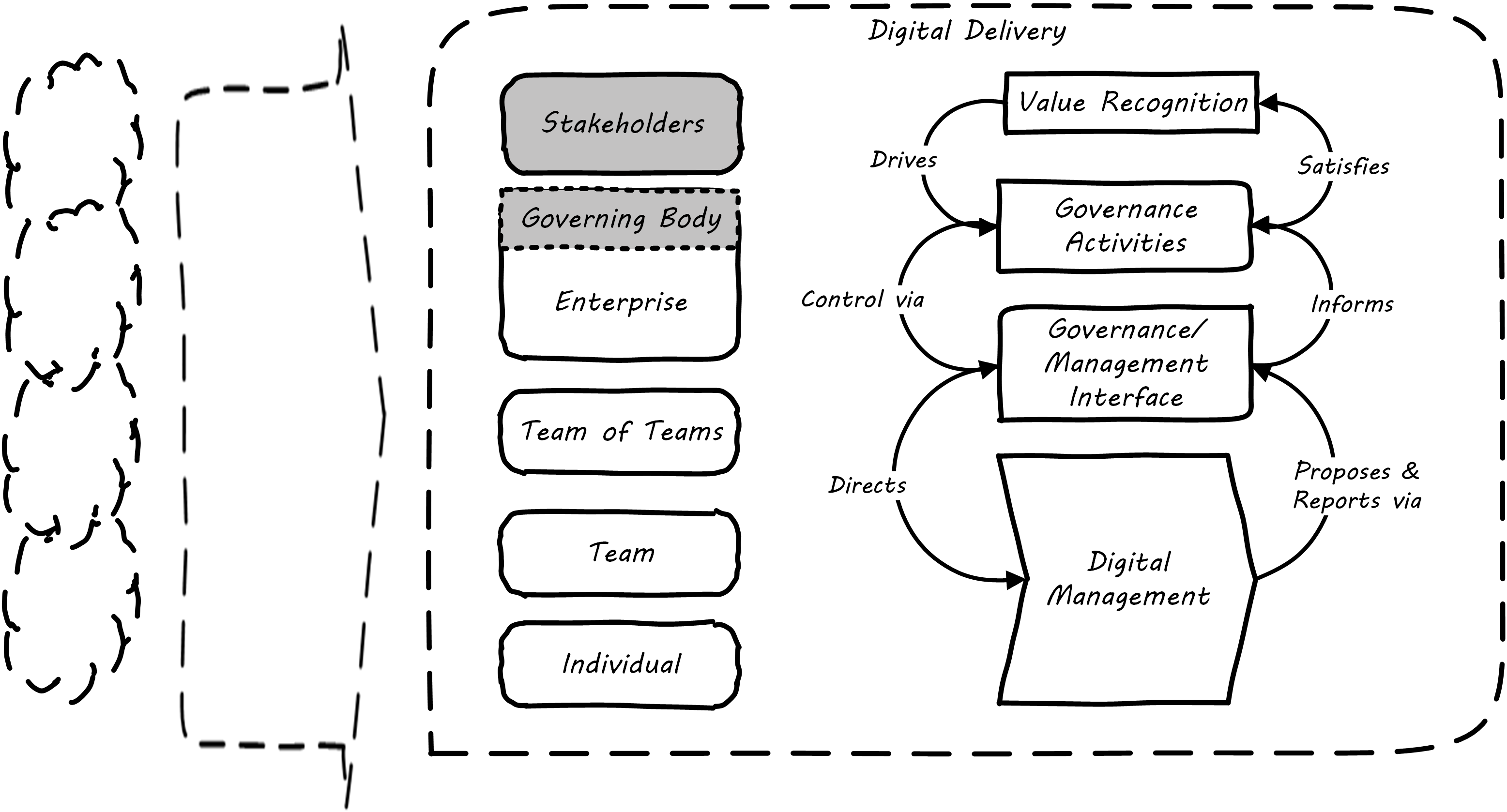

In terms of our emergence model, one of the most important distinctions between a “team of teams” and an “enterprise” is the existence of formalized organizational governance.

As illustrated in Governance Emerges at the Enterprise Level, formalized governance is represented by the establishment of a governing body, responsive to some stakeholders who seek to recognize value from the organization or “entity” – in this case, a digital delivery organization.

Corporate governance is a broad and deep topic, essential to the functioning of society and its organized participants. These include for-profit, non-profit, and even governmental organizations. Any legally organized entity of significant scope has governance needs.

One well-known structure for organizational governance is seen in the regulated, publicly owned company (such as those listed on stock exchanges). In this model, shareholders elect a governing body (usually termed the Board of Directors), and this group provides the essential direction for the enterprise as a whole.

However, organizational governance takes other forms. Public institutions of higher education may have a Board of Regents or Board of Governors, perhaps appointed by elected officials. Non-profits and incorporated private companies still require some form of governance, as well. One of the less well-known but very influential forms of governance is the venture capital portfolio approach, very different from a public, mission-driven company. We will talk more about this in the digital governance section.

These are well-known topics in law, finance, and social organization, and there are many sources you can turn to if you have further interest. If you are taking any courses in Finance or Accounting, you will likely cover governance objectives and processes.

Governance and Management with Interface[2] illustrates a more detailed visual representation of the relationship between governance and management in a digital context. Reading from the top down:

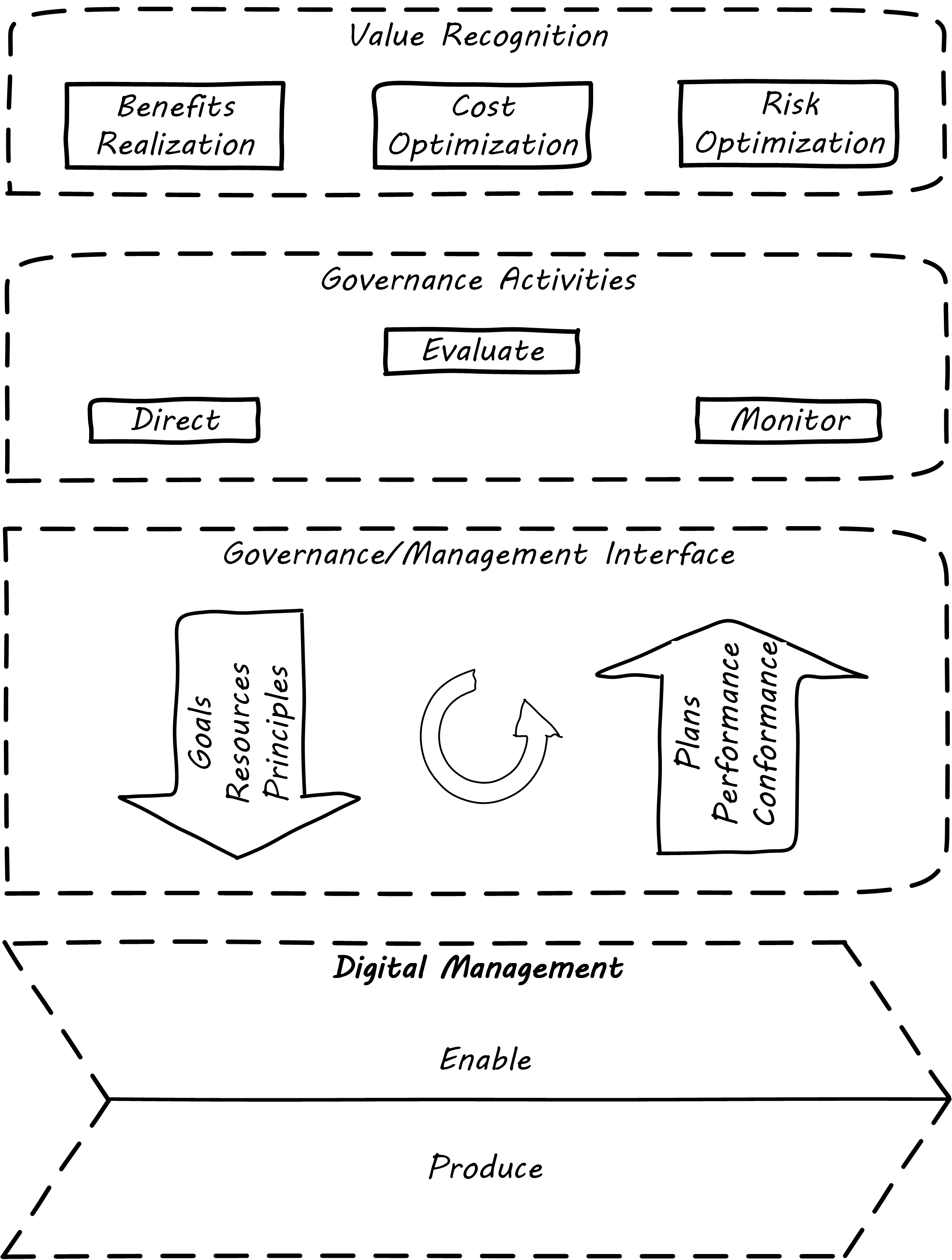

Value recognition is the fundamental objective of the stakeholder. We discussed in Product Management the value objectives of effectiveness, efficiency, and risk (aka top line, bottom line, and risk). These are useful final targets for impact mapping, to demonstrate that lower-level perhaps more “technical” product capabilities do ultimately contribute to organization outcomes.

| The term “value recognition” as the stakeholder goal is chosen over “value creation” as “creation” requires the entire system. Stakeholders do not “create” without the assistance of management, delivery teams, and the individual. |

Here, we see them from the stakeholder perspective of:

-

Benefits realization

-

Cost optimization

-

Risk optimization

(Derived from ISACA 2012)

ISO 38500 [ISO/IEC 38500:2008] and COBIT [ISACA 2012], [ISACA 2018] both specify that the fundamental governance activities of governance are:

-

Direct

-

Evaluate

-

Monitor

Evaluation is the analysis of current state, including current proposals and plans. Directing is the establishment of organizational intent as well as the authorization of resources. Monitoring is the ongoing attention to organizational status, as an input to evaluation and direction.

Direct, Evaluate, and Monitor may also be ordered as Evaluate, Direct, and Monitor (EDM). These are highly general concepts that in reality are performed simultaneously, not as any sort of strict sequence.

The governance/management interface is an essential component. The information flows across this interface are typically some form of the following:

-

From the governing side:

-

Goals (e.g., product and go-to-market strategies)

-

Resource authorizations (e.g., organizational budget approvals)

-

Principles and policies (e.g., personnel and expense policies)

-

-

From the governed side:

-

Plans and proposals (at a high level; e.g., budget requests)

-

Performance reports (e.g., sales figures)

-

Conformance/compliance indicators (e.g., via audit and assurance)

-

Notice also the circular arrow at the center of the governance/management interface. Governance is not a one-way street. Its principles may be stable, but approaches, tools, practices, processes, and so forth (what we will discuss below as "governance elements") are variable and require ongoing evolution.

We often hear of “bureaucratic” governance processes. But the problem may not be “governance” per se. It is more often the failure to correctly manage the governance/management interface. Of course, if the Board is micro-managing, demanding many different kinds of information and intervening in operations, then governance and its management response is all much the same thing. In reality, however, burdensome organizational “governance” processes may be an overdone, bottom-up management response to perceived Board-level mandates.

Or they may be point-in-time requirements no longer needed. The policies of 1960 are unsuited to the realities of 2020. But if policies are always dictated top-down, they may not be promptly corrected or retired when no longer applicable. Hence, the scope and approach of governance in terms of its elements must always be a topic of ongoing, iterative negotiation between the governed and the governing.

Finally the lowermost digital delivery chevron – aka value chain, represents most of what we have discussed in Contexts I, II, and III:

-

The individual working to create value using digital infrastructure and lifecycle pipelines

-

The team collaborating to discover and deliver valuable digital products

-

The team of teams coordinating to deliver higher-order value while balancing effectiveness with efficiency and consistency

Ultimately, governance is about managing results and risk. It is about objectives and outcomes. It is about “what”, not “how”. In terms of practical usage, it is advisable to limit the “governance” domain – including the use of the term – to a narrow scope of the Board or Director-level concerns, and the existence of certain capabilities, including:

-

Organizational policy management

-

External and internal assurance and audit

-

Risk management, including security aspects

-

Compliance

We turn to a more in depth conversation of how governance plays out across its boundary with management.

Evidence of Notability

Corporate governance is a central concern for organizations as they start to scale. Understanding its fundamentals, and especially distinguishing it from management, is critical. There is substantial evidence for this, including the very existence of ISACA as well as COSO and related organizations.

Limitations

Governance is an abstract and difficult to understand concept for people in earlier career stages. The tendency is to either lump it in with “management” in general, or equate it just with “security”.

Related Topics