Agile Software Development

Description

Waterfall Development

When a new analyst would join a large systems integrator Andersen Consulting® (now Accenture®) in 1998, they would be schooled in something called the Business Integration Method (BIM). The BIM was a classic expression of what is called “waterfall development”.

What is waterfall development? It is a controversial question. Walker Royce, the original theorist who coined the term named it in order to critique it [Royce 1970]. Military contracting and management consultancy practices, however, embraced it as it provided an illusion of certainty. The fact that computer systems until recently included a substantial component of hardware systems engineering may also have contributed.

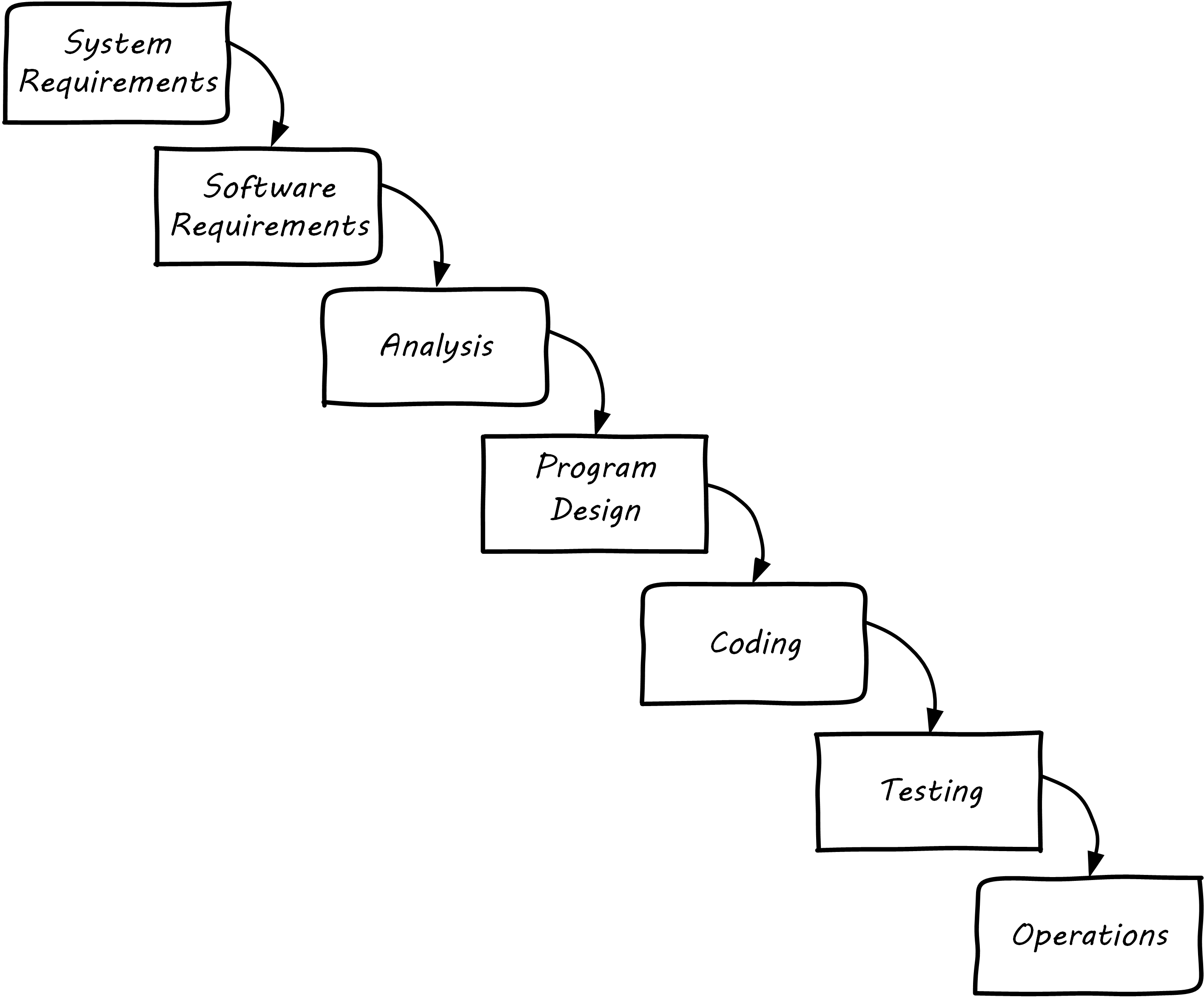

Waterfall development as a term has become associated with a number of practices. The original illustration was similar to Waterfall Lifecycle (similar to Royce 1970):

First, requirements need to be extensively captured and analyzed before the work of development can commence. So, the project team would develop enormous spreadsheets of requirements, spending weeks on making sure that they represented what “the customer” wanted. The objective was to get the customer’s signature. Any further alterations could be profitably billed as “change requests”.

The analysis phase was used to develop a more structured understanding of the requirements; e.g., conceptual and logical data models, process models, business rules, and so forth.

In the design phase, the actual technical platforms would be chosen; major subsystems determined with their connection points, initial capacity analysis (volumetrics) translated into system sizing, and so forth. (Perhaps hardware would not be ordered until this point, leading to issues with developers now being “ready”, but hardware not being available for weeks or months yet.)

Only after extensive requirements, analysis, and design would coding take place (implementation). Furthermore, there was a separation of duties between developers and testers. Developers would write code and testers would try to break it, filing bug reports to which the developers would then need to respond.

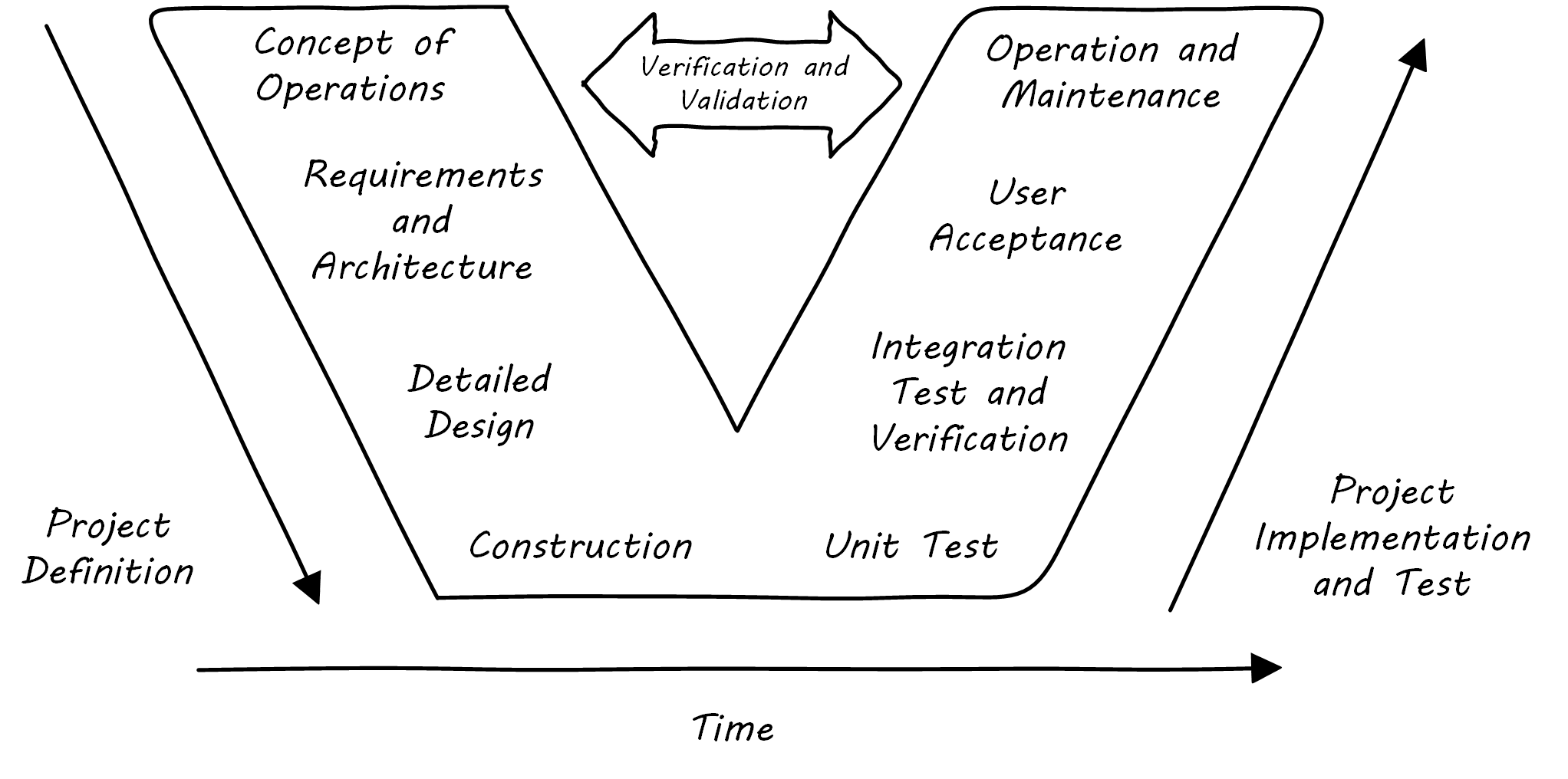

Another model sometimes encountered at this time was the V-model (see V-Model[1]). This was intended to better represent the various levels of abstraction operating in the systems delivery activity. Requirements operate at various levels, from high-level business intent through detailed specifications. It is all too possible that a system is “successfully” implemented at lower levels of specification, but fails to satisfy the original higher-level intent.

The failures of these approaches at scale are by now well known. Large distributed teams would wrestle with thousands of requirements. The customer would “sign off” on multiple large binders, with widely varying degrees of understanding of what they were agreeing to. Documentation became an end in itself and did not meet its objectives of ensuring continuity if staff turned over. The development team would design and build extensive product implementations without checking the results with customers. They would also defer testing that various component parts would effectively interoperate until the very end of the project, when the time came to assemble the whole system.

Failure after failure of this approach is apparent in the historical record [Glass 1998]. Recognition of such failures, dating from the 1960s, led to the perception of a “software crisis”.

However, many large systems were effectively constructed and operated during the “waterfall years”, and there are reasonable criticisms of the concept of a “software crisis” [Bossavit 2015].

Successful development efforts existed back to the earliest days of computing (otherwise, there probably would not be computers, or at least not so many). Many of these successful efforts used prototypes and other means of building understanding and proving out approaches. But highly publicized failures continued, and a substantial movement against “waterfall” development started to take shape.

Origins and Practices of Agile Development

By the 1990s, a number of thought leaders in software development had noticed some common themes with what seemed to work or not. Kent Beck developed a methodology known as “eXtreme Programming” (XP) [Beck & Andres 2004]. XP pioneered the concepts of iterative, fast-cycle development with ongoing stakeholder feedback, coupled with test-driven development, ongoing refactoring, pair programming, and other practices. (More details on the specifics of these can be found in the next section.)

Various authors assembled in 2001 and developed the Agile Manifesto [Agile Alliance 2001], which further emphasized an emergent set of values and practices:

The Manifesto authors further stated:

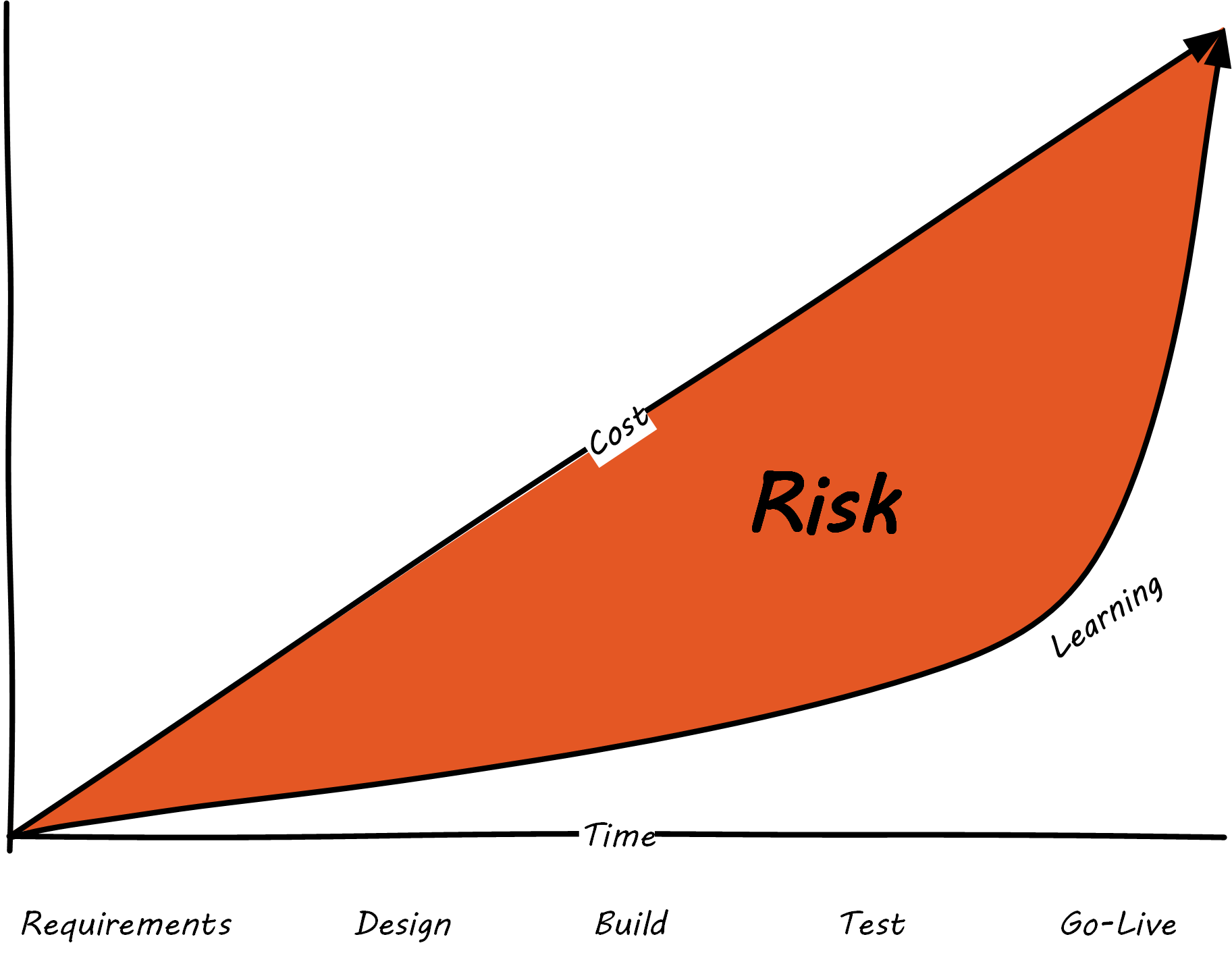

Agile methodologists emphasize that software development is a learning process. In general, learning (and the value derived from it) is not complete until the system is functioning to some degree of capability. As such, methods that postpone the actual, integrated verification of the system increase risk. Alistair Cockburn visualizes risk as the gap between the ongoing expenditure of funds and the lag in demonstrating valuable learning; see Waterfall Risk, similar to Cockburn 2012.

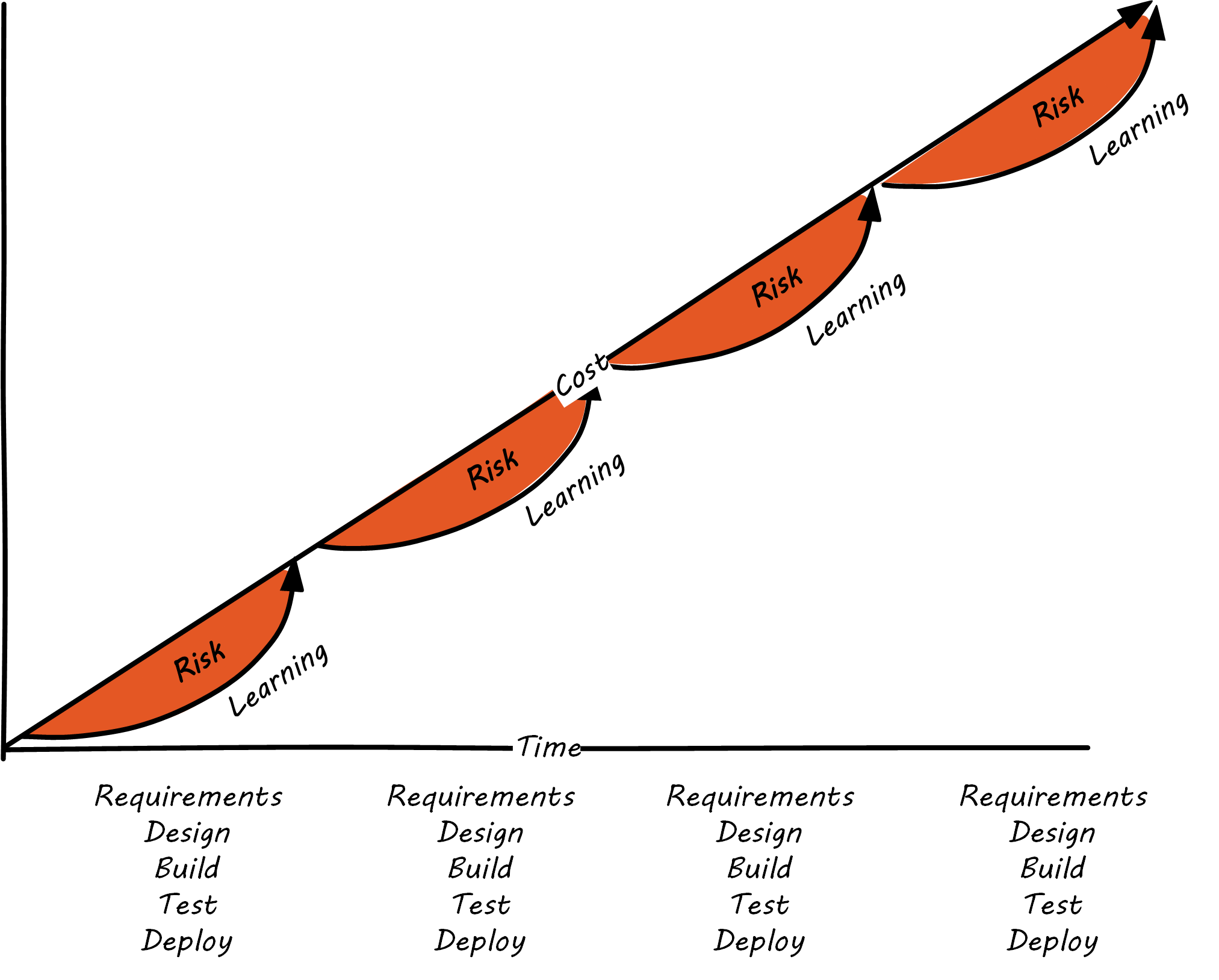

Because Agile approaches emphasize delivering smaller batches of complete functionality, this risk gap is minimized; see Agile Risk, similar to Cockburn 2012.

The Agile models for developing software aligned with the rise of cloud and web-scale IT. As new customer-facing sites like Flickr®, Amazon, Netflix, Etsy®, and Facebook scaled to massive proportions, it became increasingly clear that waterfall approaches were incompatible with their needs. Because these systems were directly user-facing, delivering monetized value in fast-moving competitive marketplaces, they required a degree of responsiveness previously not seen in “back-office” IT or military-aerospace domains (the major forms that large-scale system development had taken to date). We will talk more of product-centricity and the overall DevOps movement in the next section.

This new world did not think in terms of large requirements specifications. Capturing a requirement, analyzing and designing to it, implementing it, testing that implementation, and deploying the result to the end user for feedback became something that needed to happen at speed, with high repeatability. Requirements “backlogs” were (and are) never “done”, and increasingly were the subject of ongoing re-prioritization, without high-overhead project “change” barriers.

These user-facing, web-based systems integrate the SDLC tightly with operational concerns. The sheer size and complexity of these systems required much more incremental and iterative approaches to delivery, as the system can never be taken offline for the “next major release” to be installed. New functionality is moved rapidly in small chunks into a user-facing, operational status, as opposed to previous models where vendors would develop software on an annual or longer version cycle, to be packaged onto media for resale to distant customers.

Contract software development never gained favor in the Silicon Valley web-scale community; developers and operators are typically part of the same economic organization. So, it was possible to start breaking down the walls between “development” and “operations”, and that is just what happened.

Large-scale systems are complex and unpredictable. New features are never fully understood until they are deployed at scale to the real end user base. Therefore, large-scale web properties also started to “test in production” (more on this in the Operations Competency Area) in the sense that they would deploy new functionality to only some of their users. Rather than trying to increase testing to understand things before deployment better, these new firms accepted a seemingly higher-level of risk in exposing new functionality sooner. (Part of their belief is that it actually is lower risk because the impacts are never fully understood in any event.)

Evidence of Notability

See Larman 2003 for a thorough history of Agile and its antecedents. Agile is recognized as notable in leading industry and academic guidance [ACM/IEEE-CS 2015], [IEEE® 2014] and has a large, active, and highly visible community; refer to the Agile Alliance. It is increasingly influential on non-software activities as well [Rigby et al. 2016], [Rigby et al. 2018].

Limitations

Agile development is not as relevant when packaged software is acquired. Such software has a more repeatable pattern of implementation, and more up-front planning may be appropriate.

Related Topics