Assurance and Audit

Assurance

Trust, but verify.

Assurance is a broad term. In this document, it is associated with governance. It represents a form of additional confirmation that management is performing its tasks adequately. Go back to the example that started this Competency Area, of the shop owner hiring a manager. Suppose that this relationship has continued for some time, and while things seem to be working well, the owner has doubts about the arrangement. Over time, things have gone well enough that the owner does not worry about the shop being opened on time, having sufficient stock, or paying suppliers. But there are any number of doubts the owner might retain:

-

Is money being accounted for honestly and accurately?

-

Is the shop clean?

-

Is the shop following local regulations; for example, fire, health, and safety codes?

-

If the manager selects a new supplier, are they trustworthy – or is the shop at risk of selling counterfeit or tainted merchandise?

-

Are the shop’s prices competitive?

-

Is it still well regarded in the community, or has its reputation declined with the new manager?

-

Is the shop protected from theft and disaster?

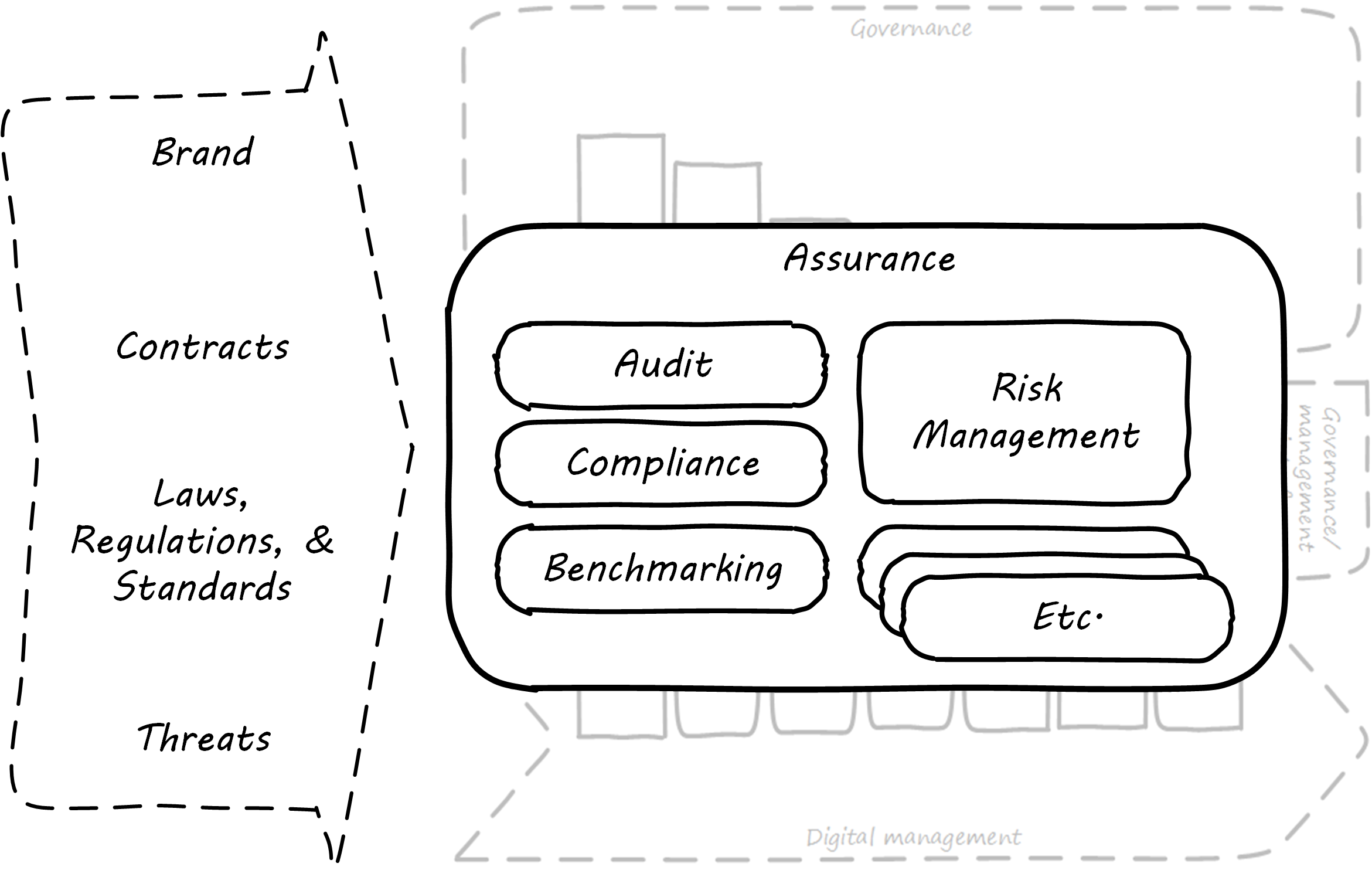

These kinds of concerns remain with the owner, by and large, even with a reliable and trustworthy manager. If not handled correctly, the owner’s entire investment is at risk. The manager may only have a salary (and perhaps a profit share) to worry about, but if the shop is closed due to violations, or lawsuit, or lost to a fire, the owner’s entire life investment may be lost. These concerns give rise to the general concept of assurance, which applies to digital business just as it does to small retail shops. Assurance is an Objective, External Mechanism, derived from previous illustrations, shows how this document views assurance: as a set of practices overlaid across governance elements, and in particular concerned with external forces; see Assurance in Context.

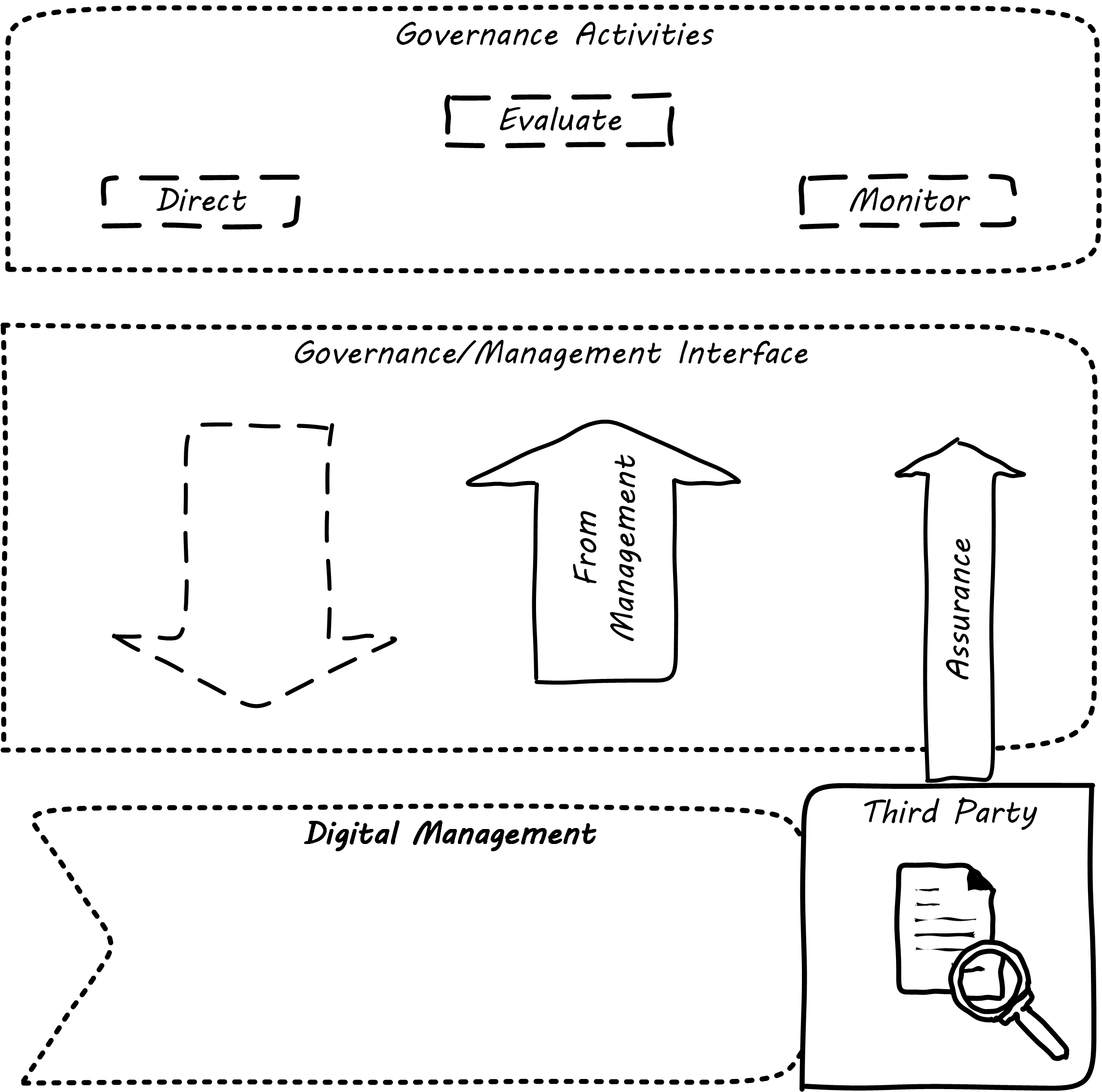

In terms of the governance-management interface, assurance is fundamentally distinct from the information provided by management and must travel through distinct communication channels. This is why auditors, for example, forward their reports directly to the Audit Committee and do not route them through the executives who have been audited.

Technologists, especially those with a background in networking, may have heard of the concept of “out-of-band control”. With regard to out-of-band management or control of IT resources, the channel over which management commands travel is distinct from the channel over which the system provides its services. This channel separation is done to increase security, confidence, and reliability, and is analogous to assurance.

As ISACA stipulates: “The information systems audit and assurance function shall be independent of the area or activity being reviewed to permit objective completion of the audit and assurance engagement.” [ISACA 2014]. Assurance can be seen as an external, additional mechanism of control and feedback. This independent, out-of-band aspect is essential to the concept of assurance; see Assurance is an Objective, External Mechanism.

Three-Party Foundation

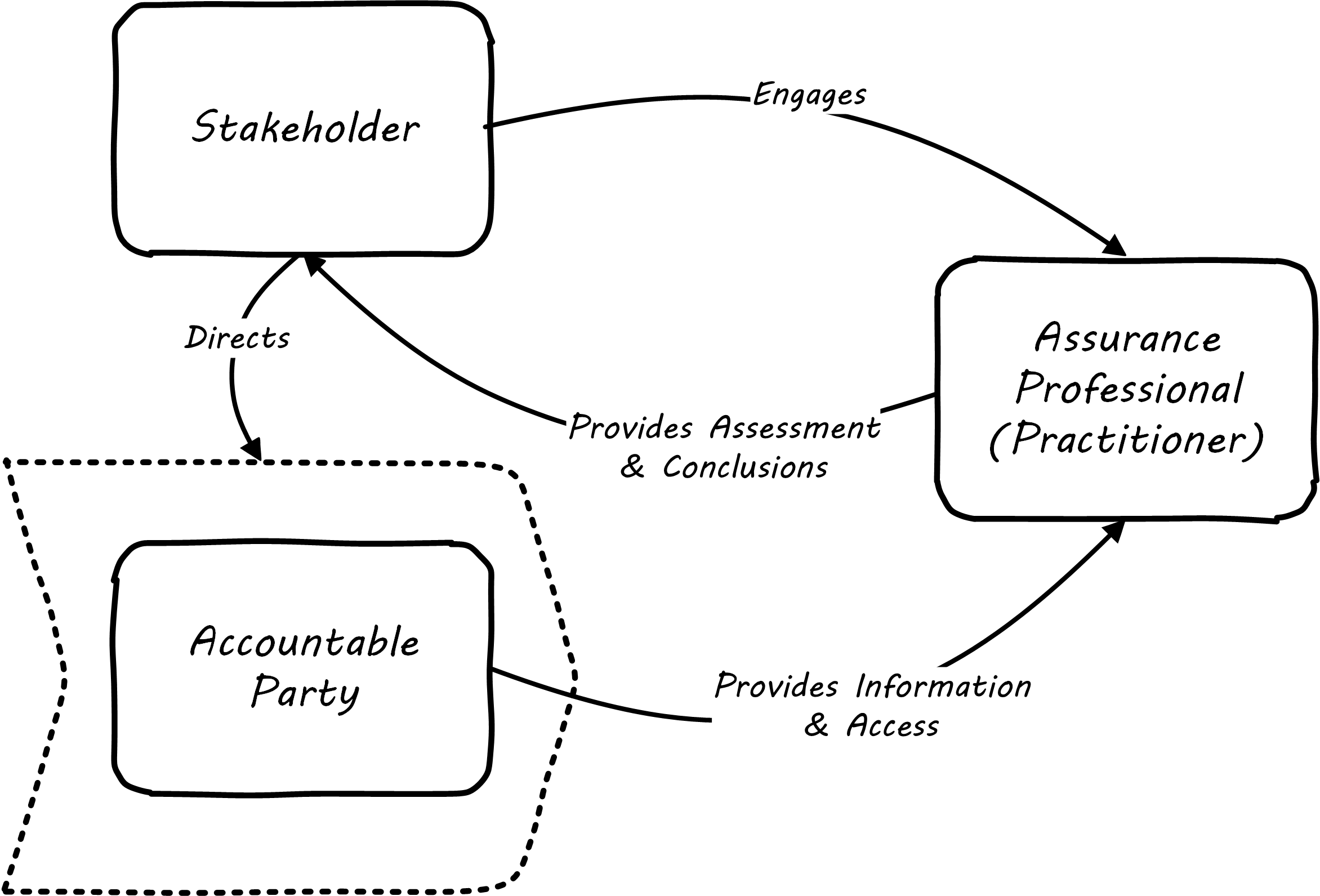

Assurance means that pursuant to an accountability relationship between two or more parties, an IT audit and assurance professional may be engaged to issue a written communication expressing a conclusion about the subject matters to the accountable party. [ISACA 2013a]

There are broader and narrower definitions of assurance. But all reflect some kind of three-party arrangement; see Assurance is Based on a Three-Party Model, illustrating concepts from ISACA 2013b and IAASB 2013.

Assurance is Based on a Three-Party Model is one common scenario:

-

The stakeholder (e.g., the Audit Committee of the Board of Directors) engages an assurance professional (e.g., an audit firm) – the scope and approach of this are determined by the engaging party, although the accountable party in practice often has input as well

-

The accountable party, at the direction, responds to the assurance professional’s inquiries on the audit topic

-

The assurance professional provides the assessment back to the engaging party, and/or other users of the report (potentially including the accountable party)

This is a simplified view of what can be a more complex process and set of relationships. The ISAE 3000 [ISAE 2013] states that there must be at least three parties to any assurance engagement:

-

The responsible (accountable) party

-

The practitioner

-

The intended users (of the assurance report)

But there may be additional parties:

-

The engaging party

-

The measuring/evaluating party (sometimes not the practitioner, who may be called on to render an opinion on someone else’s measurement)

ISAE 3000 goes on to stipulate a complex set of business rules for the allowable relationships between these parties. Perhaps the most important rule is that the practitioner cannot be the same as either the responsible party or the intended users. There must be some level of professional objectivity.

What is the difference between assurance and simple consulting? There are two major factors:

-

Consulting can be simply a two-party relationship – a manager hires someone for advice

-

Consultants do not necessarily apply strong assessment criteria

-

Indeed, with complex problems, there may not be any such criteria; assurance, in general, presupposes some existing standard of practice, or at least some benchmark external to the organization being assessed

-

Finally, the concept of assurance criteria is key. Some assurance is executed against the responsible party’s own criteria. In this form of assurance, the primary questions are “are you documenting what you do, and doing what you document?”. That is, for example, “do you have formal process management documentation? And are you following it?”.

Other forms of assurance use external criteria. A good example is the Uptime Institute’s data center tier certification criteria, discussed below. If criteria are weak or non-existent, the assurance engagement may be more correctly termed an advisory effort. Assurance requires clarity on this topic.

Types of Assurance

Exercise caution in your business affairs; for the world is full of trickery.[1]

Desiderata

The general topic of “assurance” implies a spectrum of activities. In the strictest definitions, assurance is provided by licensed professionals under highly formalized arrangements. However, while all audit is assurance, not all assurance is audit. As noted in COBIT for Assurance: “Assurance also covers evaluation activities not governed by internal and/or external audit standards” [ISACA 2013a).

This is a blurry boundary in practice, as an assurance engagement may be undertaken by auditors, and then might be casually called an “audit” by the parties involved. And there is a spectrum of organizational activities that seem at least to be related to formal assurance:

-

Brand assurance

-

Quality assurance

-

Vendor assurance

-

Capability assessments

-

Attestation services

-

Certification services

-

Compliance

-

Risk management

-

Benchmarking

-

Other forms of “due diligence”

Some of these activities may be managed primarily internally, but even in the case of internally managed activities, there is usually some sense of governance, some desire for objectivity.

From a purist perspective, internally directed assurance is a contradiction in terms. There is a conflict of interest in that in terms of the three-party model above, the accountable party is the practitioner.

However, it may well be less expensive for an organization to fund and sustain internal assurance capabilities and get much of the same benefits as from external parties. This requires sufficient organizational safeguards to be instituted. Internal auditors typically report directly to the Board-level Audit Committee and, generally, are not seen as having a conflict of interest.

In another example, an internal compliance function might report to the corporate general counsel (chief lawyer), and not to any executive whose performance is judged based on their organization’s compliance – this would be a conflict of interest. However, because the internal compliance function is ultimately under the CEO, their concerns can be overruled.

The various ways that internal and external assurance arrangements can work, and can go wrong, is a long history. If you are interested in the topic, review the histories of Enron Corporation, Worldcom, the 2008 mortgage crisis, and other such failures.

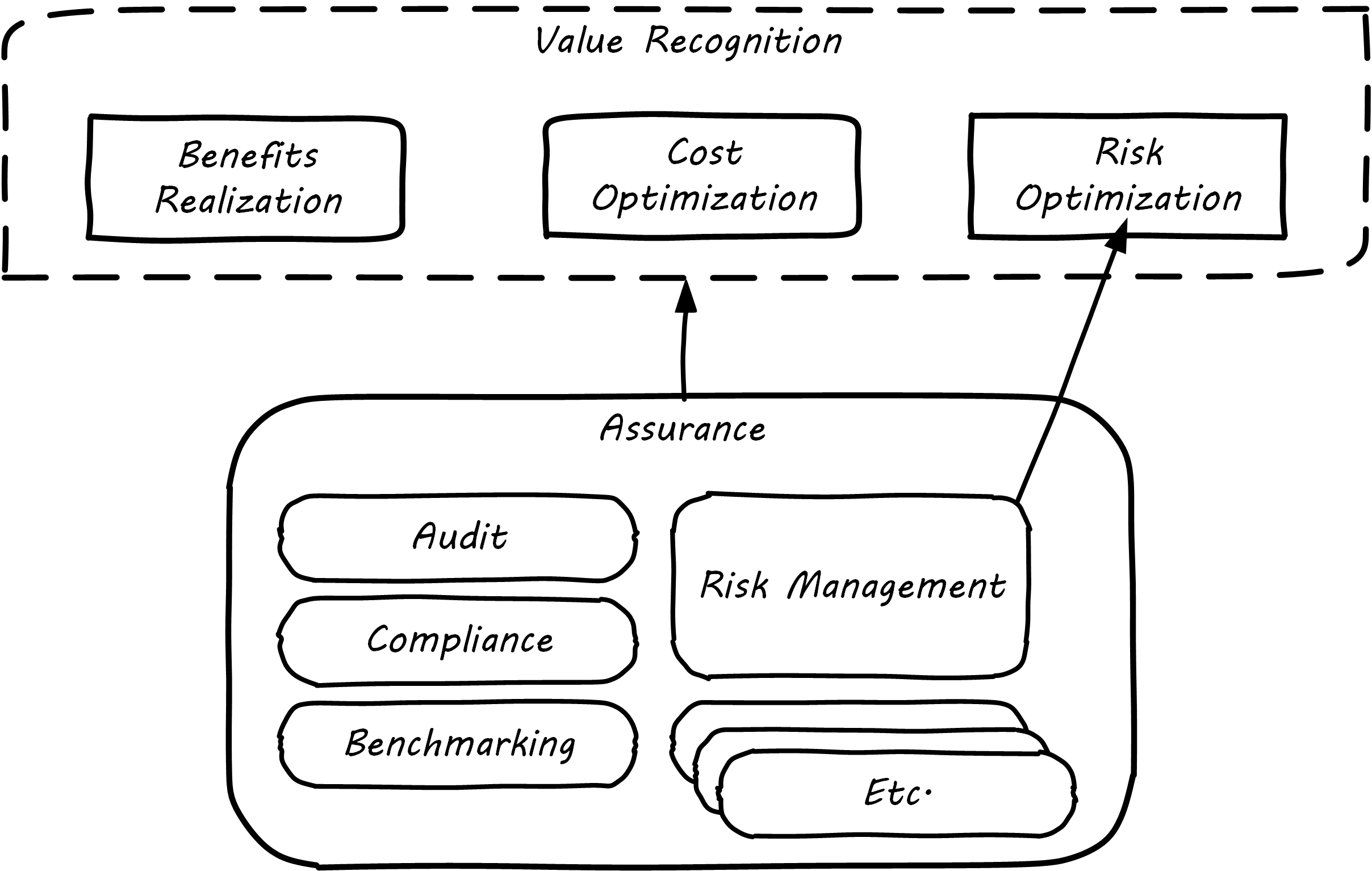

Assurance and Risk Management

Risk management (discussed in the previous section) may be seen as part of a broader assurance ecosystem. For evidence of this, consider that the Institute of Internal Auditors offers a certificate in Risk Management Assurance; The Open Group also operates the Open FAIR™ Certification Program. Assurance in practice may seem to be biased towards risk management, but (as with governance in general) assurance as a whole relates to all aspects of IT and digital governance, including effectiveness and efficiency.

Audit practices may be informed of known risks and particularly concerned with their mitigation, but risk management remains a distinct practice. Audits may have scope beyond risks, and audits are only one tool used by risk management; see Assurance and Risk Management.

In short, and as shown in the above diagram, assurance plays a role across value recognition, while risk management specifically targets the value recognition objective of risk optimization.

Non-Audit Assurance Examples

Businesses must find a level of trust between each other … third-party reports provide that confidence. Those issuing the reports stake their name and liability with each issuance. [DeLuccia 2013]

Successfully Establishing and Representing DevOps in an Audit

Before we turn to a more detailed discussion of the audit, we will discuss some specifically non-audit examples of assurance seen in IT and digital management.

Example 1: Due Diligence on a Cloud Provider

Your company is considering a major move to cloud infrastructure for its systems. The agility value proposition – the ability to minimize cost of delay – is compelling, and there may be some cost structure advantages as well.

But you are aware of some cloud failures:

-

In 2013, UK cloud provider 2e2 went bankrupt, and customers were given “24 to 48 hours to get … data and systems out and into a new environment” [duPreez 2015]; subsequently, the provider demanded nearly £1 million (roughly $1.5 million) from its customers for their uninterrupted access to services (i.e., their data) [Venkatraman 2013]

-

Also in 2013, cloud storage provider Nirvanix went bankrupt, and its customers also had a limited time to remove their data; MegaCloud went out of business with no warning two months later, and all customers lost all data [Butler 2013], [Butler 2014]

-

In mid-2014, online source code repository Cloud Spaces® (an early GitHub competitor) was taken over by hackers and destroyed; all data was lost [Venezia 2014], [Marks 2014]

The question is, how do you manage the risks of trusting your data and organizational operations to a cloud provider? This is not a new question, as computing has been outsourced to specialist firms for many years. You want to be sure that their operations meet certain standards such as:

-

Financial standards

-

Operational standards

-

Security standards

Data center evaluations of cloud providers are a form of assurance. Two well-known approaches are:

-

The Uptime Institute’s Tier Certification [Uptime 2016]

-

The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants’ (AICPA) SOC 3® Trust Services Report certifying “Service Organizations” [AICPA] (based in turn on the AICPA SSAE-18 standard)

The Uptime Institute provides the well-known “Tier” concept for certifying data centers, from Tier I to Tier IV. In their words: “certification provides assurances that there are not shortfalls or weak links anywhere in the data center infrastructure” [Uptime 2016]. The Tiers progress as follows [Uptime 2014]:

-

Tier I: Basic Capacity

-

Tier II: Redundant Capacity Components

-

Tier III: Concurrently Maintainable

-

Tier IV: Fault Tolerance

Uptime Institute certification is a generic form of assurance in terms of the three-party model; the data center operator must work with the Uptime Institute who provides an independent opinion based on their criteria as to the data center’s tier (and therefore effectiveness).

The SOC 3 report is considered an “assurance” standard as well. However, as mentioned above, this is the kind of “assurance” done in general by licensed auditors, and which might casually be called an “audit” by the participants. A qualified professional, again in the three-party model, examines the data center in terms of the AICPA SSAE-18 standard.

Your internal risk management organization might look to both Uptime Institute and SOC 3 certification as indicators that your cloud provider risk is mitigated. (More on this in Risk and Compliance Management.)

Example 2: Internal Process Assessment

You may also have concerns about your internal operations. Perhaps your process for selecting technology vendors is unsatisfactory in general; it takes too long and yet vendors with critical weaknesses have been selected. More generally, the actual practices of various areas in your organization may be assessed by external consultants using the related guidance:

-

Enterprise Architecture with the TOGAF Architecture Development Method (ADM)

-

Project Management with PMBOK

-

IT processes such as incident management, change management, and release management with ITIL or CMMI-SVC

These assessments may be performed through using a maturity scale; e.g., CMM-derived. The CMM-influenced ISO/IEC 15504-5:2012 may be used as a general process assessment framework. (Remember that we have discussed the problems with the fundamental CMM assumptions on which such assessments are based.)

According to Bente et al.: “In our own experience, we have seen that the maturity models have their limitations” [Bente et al. 2012]. They warn that maturity assessments of Enterprise Architecture at least are prone to being:

-

Subjective

-

Academic

-

Easily manipulated

-

Bureaucratic

-

Superfluous

-

Misleading

Those issues may well apply to all forms of maturity assessments. Let the buyer beware. At least, the concept of maturity should be very carefully defined in a manner relevant to the organization being assessed.

Example 3: Competitive Benchmarking

Finally, you may wonder: “How does my digital operation compare to other companies?” Now, it is difficult to go to a competitor and ask this. It is also not especially practical to go and find some non-competing company in a different industry you do not understand well. An entire industry has emerged to assist with this question.

We talked about the role of industry analysts in Investment and Portfolio. Benchmarking firms play a similar role and, in fact, some analyst firms provide benchmarking services.

There are a variety of ways benchmarking is conducted, but it is similar to assurance in that it often follows the three-party model. Some stakeholder directs an accountable party to be benchmarked within some defined scope. For example, the number of staff required to managed a given quantity of servers (aka admin:server) has been a popular benchmark. (Note that with cloud, virtualization, and containers, the usefulness of this metric is increasingly in question.)

An independent authority is retained. The benchmarker collects, or has collected, information on similar operations; for example, they may have collected data from 50 organizations of similar size on admin:server ratios. This data is aggregated and/or anonymized so that competitive concerns are reduced. Wells Fargo® will not be told: “JP Morgan Chase™ has an overall ratio of 1:300”; they will be told: “The average for financial services is 1:250”.

In terms of formal assurance principles, the benchmark data becomes the assessment criteria. A single engagement might consider dozens of different metrics, and where simple quantitative ratios do not apply, the benchmarker may have a continuously maintained library of case studies for more qualitative analysis. This starts to shade into the kind of work also performed by industry analysts. As the work becomes more qualitative, it also becomes more advisory and less about “assurance” per se.

Audit

The Committee, therefore, recommends that all listed companies should establish an Audit Committee. [Cadbury 1992]

Agile or not, a team ultimately has to meet legal and essential organizational needs and audits help to ensure this. [Ambler & Lines 2012]

Disciplined Agile Delivery

If you look up “audit” online or in a dictionary, you will see it mainly defined in terms of finance: an audit is a formal examination of an organization’s finances (sometimes termed “books”). Auditors look for fraud and error so that investors (like our shop owner) have confidence that accountable parties (e.g., the shop manager) are conducting business honestly and accurately.

Audit is critically important to the functioning of the modern economy because there are great incentives for theft and fraud, and owners (in the form of shareholders) are remote from the business operations.

But what does all this have to do with IT and Digital Transformation?

Digital organizations, of course, have budgets and must account for how they spend money. Since financial accounting and its associated audit practices are a well-established practice, we will not discuss it here. (We discussed IT financial management and service accounting in Financial Management of Digital and IT.)

Money represents a form of information – that of value. Money once was stored as a precious metal. When carrying large amounts of precious metal became impossible, it was stored in banks and managed through paper record-keeping. Paper record-keeping migrated onto computing machines, which now represent the value once associated with gold and silver. Bank deposits (our digital user’s bank account balance from Digital Value) are now no more than a computer record – digital bits in memory – made meaningful by tradition and law, and secured through multiple layers of protection and assurance.

Because of the increasing importance of computers to financial fundamentals, auditors became increasingly interested in IT. Clearly, these new electronic computers could be used to commit fraud in new and powerful ways. Auditors had to start asking: “How do you know the data in the computer is correct?”. This led to the formation in 1967 of the Electronic Data Processing Auditors Association (EDPAA), which eventually became IS Audit and Control Association (ISACA) (developer of COBIT).

It also became clear that computers and their associated operation were a notable source of cost and risk for the organization, even if they were not directly used for financial accounting. This has led to the direct auditing of IT practices and processes, as part of the broader assurance ecosystem we are discussing in this Competency Category.

A wide variety of IT practices and processes may be audited. Auditors may take a general interest in whether the IT organization is “documenting what it does and doing what it documents” and therefore nearly every IT process has been seen to be audited.

IT auditors may audit projects, checking that the expected project methodology is being followed. They may audit IT performance reporting, such as claims of meeting SLAs. And they audit the organization’s security approach – both its definition of security policies and controls, as well as their effectiveness.

IT processes supporting the applications used by financially-relevant systems, in general, will be under the spotlight from an auditor. This is where Information Technology General Controls (ITGCs) play a key role to assure that the data is secured and is reliable for financial reporting. The IT Governance Institute [ITGI 2006] further articulates how IT controls and the technology environment’s relationship between the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) and COBIT is built.

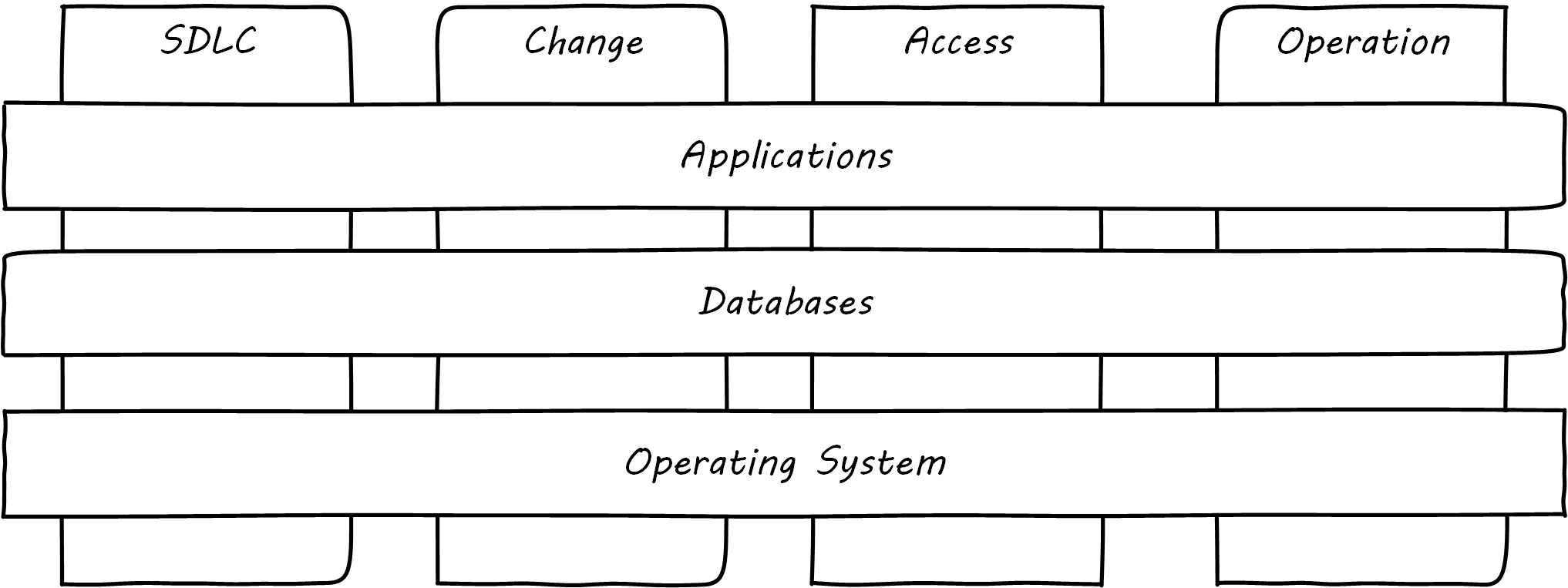

Adapted from IT Control environment [ITGI 2006, Figure 1]

Logical access to data, changes to applications, development of application, and computer operations will be the key areas of focus. Each of these areas are further divided into sub-areas for controlling the environment effectively.

Areas of control, generally, fall into these categories: SDLC, change management, logical access, and operations. A brief note on each of these controls follows:

-

SDLC

If changes done to applications involve data conversion, management approval should be documented before moving the code to production, irrespective of the development methodology chosen. Controls could be called:

-

Data conversion testing

-

Go-live approval

-

-

Change management

Changes to the applications need to be tested with the appropriate level of documentation and approved through a Change Control Board. Management need to ensure that developers do not have privileged access to the production environment, including code migration privileges. Controls could be called:

-

Change testing

-

Change approval

-

Developer no privileged production access

-

Developer/migrator access

-

-

Logical Access

Access to the applications need to be controlled through a variety of controls, such as provisioning and deprovisioning of access; password complexity and generic identity; password management; and access review of privileged/generic accounts and user accesses. Though not an extensive list, management oversight across the board is needed when users are involved to ensure the appropriate level of access is given and monitored. Controls could be called:

-

Password settings

-

User access reviews

-

Role reviews

-

Generic account password changes

-

Access review – privileged account

-

Access review – generic accounts

-

Access provisioning

-

Access removal

-

-

Operations

In IT organizations, another key activity is to maintain and manage the infrastructure supporting the data: who has access to the data center, how we schedule jobs, what we do when jobs fail, how we take backups and restore from backups, when needed, and form key sub-areas to manage. Controls could be called:

-

Data center access

-

Job scheduling and resolution

-

Data backups

-

Data restoration

-

Controls driven through policies and processes target the application landscape, which helps financial reporting. Care needs to be taken to ensure that the prevention or detection controls are executed in a timely manner. As an example, Logical Access – Access Provisioning is deemed a preventative control; i.e., preventing unnecessary access to data, and Logical Access – User Access Review is deemed a detective control; i.e., detecting access provisioned is still relevant. Each control needs to be evaluated on its merit and ensure that there are mitigating controls.

If you are in a public company, IT controls relate directly to the SEC 10K report – an annual filing of the company’s financial status. The formation of this report is a culmination of the various audits conducted by internal and external auditors. Internal control over financial reporting by the PCAOB [PCAOBUS 2007] clearly notes the implications of the control environment.

| Controls failure is an ongoing theme in The Phoenix Project [Kim et al. 2013], the novelization that helped launch DevOps as a movement. |

If the controls start to fail, the scale of control failure ranges from an individual application failing any of the control to system design failure or the operational failure of the control [PCAOBUS 2007] standard notes that the severity of the failure as a control is deficient – a combination of deficiencies leading to significant deficiency and a combination of deficiencies with potential for misstatement of financial reporting leading to material weakness. There should be enough management attention for each of these control failures and it may include application owner, control owner, and CIO including the Audit Committee of the Board of Directors.

Organizations need to survive in the digital economy by making choices with the limited pool of budget available. If the IT organization cannot control the environment, the cost of compliance significantly increases, thereby reducing the investment available for innovation.

It is better to be compliant to innovate more!

External versus Internal Audit

There are two major kinds of auditors of interest to us:

-

External auditors

-

Internal auditors

An external auditor can be defined as someone who is “chartered by a regulatory authority to visit an enterprise or entity and to review and independently report the results of that review.” [Moeller 2013].

Many accounting firms offer external audit services, and the largest accounting firms (such as PriceWaterhouse Coopers and EY) provide audit services to the largest organizations (corporations, non-profits, and governmental entities). External auditors are usually certified public accountants, licensed by their state, and following industry standards (e.g., from the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants).

By contrast, internal auditing is housed internally to the organization, as defined by the Institute of Internal Auditors: “Internal auditing is an independent appraisal function established within an organization to examine and evaluate its activities as a service to the organization” [Moeller 2013].

Internal audit is considered a distinct but complementary function to external audit [Cadbury 1992]. The internal audit function usually reports to the Audit Committee. As with assurance in general, independence is critical – auditors must have organizational distance from those they are auditing, and must not be restricted in any way that could limit the effectiveness of their findings.

Audit Practices

As with other forms of assurance, audit follows the three-party model. There is a stakeholder, an accountable party, and an independent practitioner. The typical internal audit lifecycle consists of (derived from ISACA 2013a):

-

Planning/scoping

-

Performing

-

Communicating

In the scoping phase, the parties are identified (e.g., the Board Audit Committee, the accountable and responsible parties, the auditors, and other stakeholders).

The scope of the audit is very specifically established, including objectives, controls, and various governance elements (e.g., processes) to be tested. Appropriate frameworks may be utilized as a basis for the audit, and/or the organization’s own process documentation.

The audit is then performed. A variety of techniques may be used by the auditors:

-

Performance of processes or their steps

-

Inspection of previous process cycles and their evidence (e.g., documents, recorded transactions, reports, logs, etc.)

-

Interviews with staff

-

Physical inspection or walkthroughs of facilities

-

Direct inspection of system configurations and validation against expected guidelines

-

Attempting what should be prevented (e.g., trying to access a secured system or view data over the authorization level)

A fundamental principle is “expected versus actual”. There must be some expected result to a process step, calculation, etc., to which the actual result can be compared.

Finally, the audit results are reported to the agreed users (often with a preliminary “heads up” cycle so that people are not surprised by the results). Deficiencies are identified in various ways and typically are taken into system and process improvement projects.

Evidence of Notability

Assurance as a broad topic, and audit as a narrower instance, like governance itself are fundamental to the functioning of the economy. ISACA has published significant guidance on both topics, as have other, broader organizations such as the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB).

Limitations

Assurance and audit in general require some clear standard or expectation against which to assess. In terms of process, they are suitable for lower-variability problem domains. They are less applicable to complex or chaotic domains. However, even within a chaotic situation, there will still be basic assumptions around, for example, how money and security are to be handled. Audit, in the IT systems context, has been important enough to drive the creation of one of the major IT/Digital Practitioner organizations, the ISACA (founded in 1967 as the EDPAA).

Related Topics