Coordination Principles and Techniques

Description

As an organization scales, there is an increasing span in its time horizon and the scope of work it considers and executes. Evolving from the immediate, “hand-to-mouth” days of a startup, it now must concern itself with longer and longer timeframes: contracts, regulations, and the company’s strategy as it grows all demand this.

Granularity

The terminology used to describe work also becomes more diverse, reflecting in some ways the broader time horizons the organization is concerned with. Requests, changes, incidents, work orders, releases, stories, features, problems, major incidents, epics, refreshes, products, programs, strategies; there is a continuum of terminology from small to large. Mostly, the range of work seems tied to how much planning time is available, but there are exceptions: disasters take a lot of work, but do not provide much advance warning! So the size of work is independent of the planning horizon.

This is significantly evolved since the earlier discussion of work management. By the time the organization started to formalize operations, work was tending to differentiate. Still, regardless of the label put on a given activity, it represents some set of tasks or objectives that real people are going to take the time to perform, and expect to be compensated for. It is all demand, requiring management. Remembering this is essential to digital management.

And, as organizations scale, dependencies proliferate: the central topic of this Competency Area.

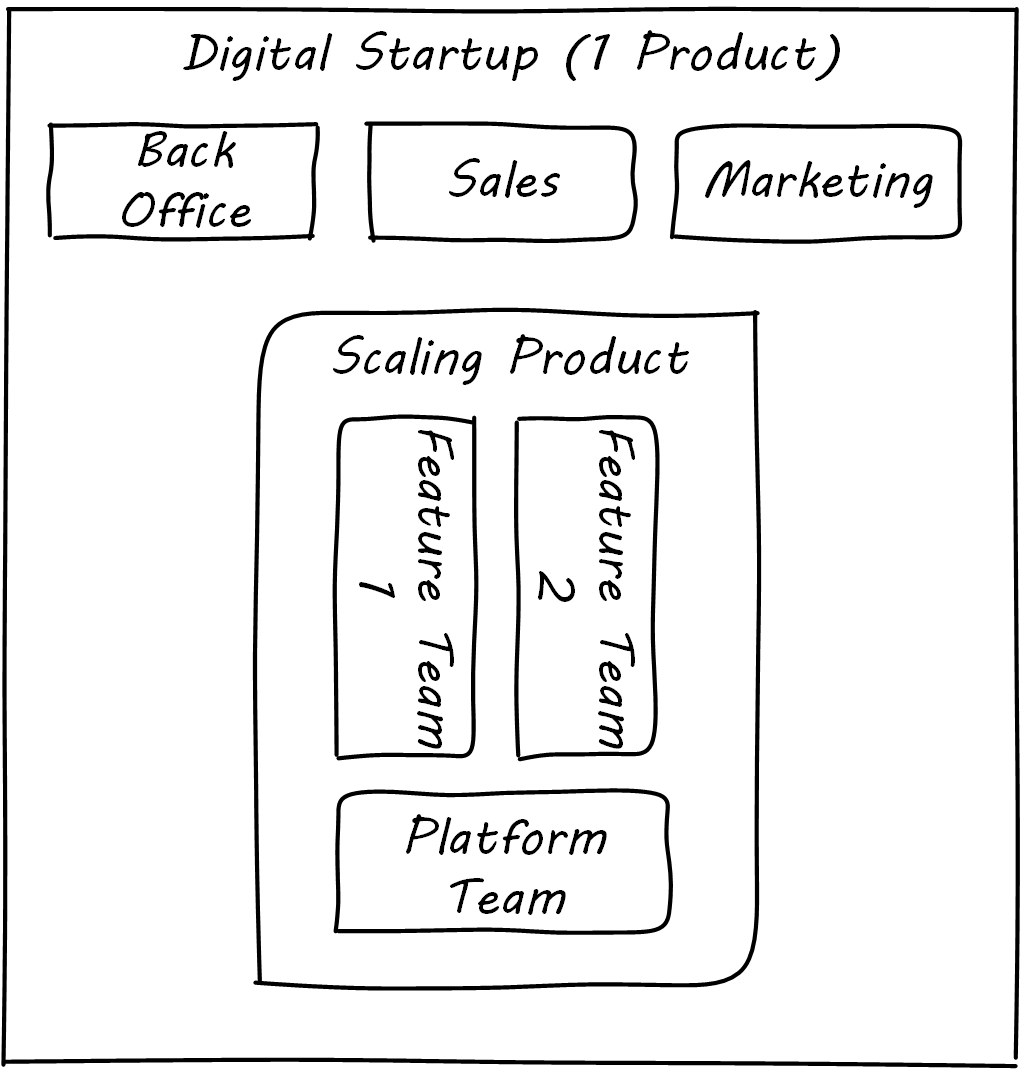

Example: Scaling One Product

Good team structure can go a long way toward reducing dependencies but will not eliminate them. [Cohn 2009]

Succeeding with Agile

What’s typically underestimated is the complexity and indivisibility of many large-scale coordination tasks. [Whitehurst 2015]

Foreword Contributer to The Open Organization: Igniting Passion and Performance

With the move to team of teams, the organization is now executing in a more complex environment; it has started to scale along the AKF scaling cube y-axis, and has either multiple teams working on one product and/or multiple products. Execution becomes more than just “pull another story off the Kanban board”. As multiple teams are formed (see Multiple Feature Teams, One Product), dependencies arise, and we need coordination. The term “architecture” is likely emerging through these discussions. (We will discuss organizational structure directly in Structuring the Organization: Product and Function, and architecture in Architecture and Portfolio.)

As noted in the discussion of Amazon’s product strategy, some needs for coordination may be mitigated through the design of the product itself. This is why APIs and microservices are popular architecture styles. If the features and components have well-defined protocols for their interaction and clear contracts for matters like performance, development on each team can move forward with some autonomy.

But at scale, complexity is inevitable. What happens when a given business objective requires a coordinated effort across multiple teams? For example, an online e-commerce site might find itself overwhelmed by business success. Upgrading the site to accommodate the new demand might require distinct development work to be performed by multiple teams; see Coordinated Initiative Across Timeframes.

As the quote from Gary Hamel above indicates, a central point of coordination and accountability is advisable. Otherwise, the objective is at risk. (It becomes “someone else’s problem”.) We will return to the investment and organizational aspects of multi-team and multi-product scaling in Investment and Portfolio and Organization and Culture. For now, we will focus on dependencies and operational coordination.

A Deeper Look at Dependencies

Coordination can be seen as the process of managing dependencies among activities. [Malone & Crowston 1994]

The Interdisciplinary Study of Coordination

What is a “dependency”? We need to think carefully about this. According to the quote above, without dependencies, we do not need coordination. (We will look at other definitions of coordination in the next two Competency Areas.) Strode & Huff 2012 have described a comprehensive framework for thinking about dependencies and coordination, including a dependency taxonomy, an inventory of coordination strategies, and an examination of coordination effectiveness criteria.

To understand dependencies, Strode et al. propose the framework shown in Dependency Taxonomy (from Strode) (adapted from Strode et al. 2012a).

| Type | Dependency | Description |

|---|---|---|

Knowledge. A knowledge dependency occurs when a form of information is required in order for progress. |

Requirement |

Domain knowledge or a requirement is not known and must be located or identified. |

Expertise |

Technical or task information is known only by a particular person or group. |

|

Task allocation |

Who is doing what, and when, is not known. |

|

Historical |

Knowledge about past decisions is needed. |

|

Task. A task dependency occurs when a task must be completed before another task can proceed. |

Activity |

An activity cannot proceed until another activity is complete. |

Business process |

An existing business process causes activities to be carried out in a certain order. |

|

Resource. A resource dependency occurs when an object is required for progress. |

Entity |

A resource (person, place, or thing) is not available. |

Technical |

A technical aspect of development affects progress, such as when one software component must interact with another software component. |

We can see examples of these dependencies throughout digital products. In the next section, we will talk about coordination techniques for managing dependencies.

Organizational Tools and Techniques

Our previous discussion of work management was a simple, idealized flow of uniform demand (new product functionality, issues, etc.). Tasks, in general, did not have dependencies, or dependencies were handled through ad hoc coordination within the team. We also assumed that resources (people) were available to perform the tasks; resource contention, while it certainly may have come up, was again handled through ad hoc means. However, as we scale, simple Kanban and visual Andon are no longer sufficient, given the nature of the coordination we now require. We need a more diverse and comprehensive set of techniques.

| The discussion of particular techniques is always hazardous. People will tend to latch on to a promising approach without full understanding. As noted by Craig Larman, the risk is one of cargo cult thinking in your process adoption [Larman & Vodde 2008]. In Organization and Culture we will discuss Toyota Kata: Managing People for Improvement, Adaptiveness, and Superior Results [Rother 2010]. Toyota does not implement any procedural change without fully understanding the “target operating condition” – the nature of the work and the desired changes to it. |

As we scale up, we see that dependencies and resource management have become defining concerns. However, we retain our Lean Product Development concerns for fast feedback and adaptability, as well as a critical approach to the idea that complex initiatives can be precisely defined and simply executed through open-loop approaches. In this section, we will discuss some of the organizational responses (techniques and tools) that have emerged as proven responses to these emergent issues.

| Coordination Taxonomy (from Strode) uses the concept of artifact, which we introduced in Work Management. For our purposes here, an artifact is a representation of some idea, activity, status, task, request, or system. Artifacts can represent or describe other artifacts. Artifacts are frequently used as the basis of communication. |

Strode et al. also provide a useful framework for understanding coordination mechanisms, excerpted and summarized into Coordination Taxonomy (from Strode) (adapted from Strode 2012).

| Strategy | Component | Definition |

|---|---|---|

Structure |

Proximity |

Physical closeness of individual team members. |

Availability |

Team members are continually present and able to respond to requests for assistance or information. |

|

Substitutability |

Team members are able to perform the work of another to maintain time schedules. |

|

Synchronization |

Synchronization activity |

Activities performed by all team members simultaneously that promote a common understanding of the task, process, and/or expertise of other team members. |

Synchronization artifact |

An artifact generated during synchronization activities. |

|

Boundary spanning |

Boundary spanning activity |

Activities (team or individual) performed to elicit assistance or information from some unit or organization external to the project. |

Boundary spanning artifact |

An artifact produced to enable coordination beyond the team and project boundaries. |

|

Coordinator role |

A role taken by a project team member specifically to support interaction with people who are not part of the project team but who provide resources or information to the project. |

The following sections expand the three strategies (structure, synchronization, boundary spanning) with examples.

Structure

Don Reinertsen proposes “The Principle of Colocation” which asserts that “colocation improves almost all aspects of communication” [Reinertsen 2009]. In order to scale this beyond one team, we logically need what Mike Cohn calls “The Big Room” [Cohn 2009].

In terms of communications, this has significant organizational advantages. Communications are as simple as walking over to another person’s desk or just shouting out over the room. It is also easy to synchronize the entire room, through calling for everyone’s attention. However, there are limits to scaling the “Big Room” approach:

-

Contention for key individuals' attention

-

“All hands” calls for attention that actually interests only a subset of the room

-

Increasing ambient noise in the room

-

Distracting individuals from intellectually demanding work requiring concentration, driving multi-tasking and context-switching, and ultimately interfering with their personal sense of flow – a destructive outcome; see Csikszentmihalyi 1990 for more on flow as a valuable psychological state

The tension between team coordination and individual focus will likely continue. It is an ongoing topic in facilities design.

Synchronization

If the team cannot work all the time in one room, perhaps they can at least be gathered periodically. There is a broad spectrum of synchronization approaches:

All of them are essentially similar in approach and assumption: build a shared understanding of the work, objectives, or mission among smaller or larger sections of the organization, through limited-time face-to-face interaction, often on a defined time interval.

Cadenced Approaches

When a synchronization activity occurs on a timed interval, this can be called a cadence. Sometimes, cadences are layered; for example, a daily standup, a weekly review, and a monthly Scrum of Scrums. Reinertsen calls this harmonic cadencing [Reinertsen 2009]. Harmonic cadencing (monthly, quarterly, and annual financial reporting) has been used in financial management for a long time.

Boundary Spanning

Examples of boundary-spanning liaison and coordination structures include:

Shared team members are suggested when two teams have a persistent interface requiring focus and ownership. When a product has multiple interfaces that emerge as a problem requiring focus, an integration team may be called for. Coordination roles can include project and program managers, release train conductors, and the like. Communities of practice will be introduced in Organization and Culture when we discuss the Spotify model. Considered here, they may also play a coordination role as well as a practice development/maturity role.

Finally, the idea of a Scrum of Scrums is essentially a representative or delegated model, in which each Scrum team sends one individual to a periodic coordination meeting where matters of cross-team concern can be discussed and decisions made; see Cohn 2009, Chapter 17.

Mike Cohn cautions: “A Scrum of Scrums meeting will feel nothing like a daily Scrum despite the similarities in names. The daily Scrum is a synchronization meeting: individual team members come together to communicate about their work and synchronize their efforts. The Scrum of Scrums, on the other hand, is a problem-solving meeting and will not have the same quick, get-in-get-out tone of a daily Scrum” [Cohn 2009].

Another technique mentioned in The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right [Gawande 2011] is the submittal schedule. Some work, while detailed, can be planned to a high degree of detail (i.e., the “checklists” of the title). However, emergent complexity requires a different approach – no checklist can anticipate all eventualities. In order to handle all the emergent complexity, the coordination focus must shift to structuring the right communications. In examining modern construction industry techniques, Gawande noted the concept of the “submittal schedule”, which “did not specify construction tasks; it specified communication tasks” (p.65, emphasis supplied). With the submittal schedule, the project manager tracks that the right people are talking to each other to resolve problems – a key change in focus from activity-centric approaches.

We have previously discussed APIs in terms of Amazon's product strategy. They are also important as a product scales into multiple components and features; API standards can be seen as a boundary-spanning mechanism.

The above discussion is by no means exhaustive. A wealth of additional techniques relevant for Digital Practitioners is to be found in Larman & Vodde 2008 and Cohn 2009. New techniques are continually emerging from the front lines of the digital profession; interested individuals should consider attending industry conferences such as those offered by the Agile Alliance.

In general, the above approaches imply synchronized meetings and face-to-face interactions. When the boundary-spanning approach is based on artifacts (often a requirement for larger, decentralized enterprises), we move into the realms of process and project management. Approaches based on routing artifacts into queues often receive criticism for introducing too much latency into the product development process. When artifacts such as work orders and tickets are routed for action by independent teams, prioritization may be arbitrary (not based on business value; e.g., cost of delay). Sometimes the work must flow through multiple queues in an uncoordinated way. Such approaches can add dangerous latency to high-value processes, as we warned in Work Management. We will look in more detail at process management in a later section.

Coordination Effectiveness

Diane Strode and her colleagues propose that coordination effectiveness can be understood as the following taxonomy:

-

Implicit

-

Knowing why (shared goal)

-

Knowing what is going on and when

-

Knowing what to do and when

-

Knowing who is doing what

-

Knowing who knows what

-

-

Explicit

-

Right place

-

Right thing

-

Right time

-

Coordinated execution means that teams have a solid common ground of what they are doing and why, who is doing it, when to do it, and where to go for information. They also have the material outcomes of the right people being in the right place doing the right thing at the right time. These coordination objectives must be achieved with a minimum of waste, and with a speed supporting an OODA loop tighter than the competition’s. Indeed, this is a tall order!

Evidence of Notability

The emergence of coordination concerns in response to organizational scaling is a common topic in Agile literature; see, for example, Larman & Vodde 2008 and Cohn 2009.

Limitations

Coordination introduces overhead. Beyond a certain point, it becomes infeasible to coordinate across all dependencies.

Related Topics