Why Culture Matters

Description

“Culture” is a difficult term to define, and even more difficult to characterize across large organizations. It starts with how an organization is formally structured, because structure is, in part, a set of expectations around how information flows. “Who talks to who, when and why” is in a sense culture. Culture can also be seen embedded in artifacts like processes and formally specified operating models.

But “culture” has additional, less tangible meanings. The anecdotes executives choose to repeat are culture. Whether an organization tacitly condones being five minutes late for meetings (because walk time in large facilities is expected) or has little tolerance for this (because most people dial in) is culture. The degree of deference shown to senior executives, and their opinions, is culture. Whether a junior person dares to hit “reply-all” on an email including her boss’s boss is culture. Organizational tolerance for competitive or toxic behavior is culture.

Culture cannot be directly changed – it is better seen as a lagging indicator, that changes in response to specific practical interventions. Even tools and processes can change the culture, if they are judiciously chosen (most tools and processes do not have this effect). Skeptical? Consider the impact that computers – a tool – have had on culture. Or email.

We have already touched on culture in the Product Management discussion of team formation. These themes of psychological safety, equal collaboration, emotional awareness, and diversity inform our further discussions. We will look at culture from a few additional perspectives in this section:

Motivation

One of the most important reasons to be concerned about culture is its effect on motivation. There is little doubt that a more motivated team performs better than an unmotivated, “going through the motions” organization. But what motivates people?

One of the oldest discussions of culture is Douglas McGregor’s idea of “Theory X” versus “Theory Y” organizations, which he developed in the 1960s at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“Theory X” organizations rely on extrinsic motivators and operate on the assumption that workers must be cajoled and punished in order to produce results. We see Theory X approaches when organizations focus on pay scales, bonuses, titles, awards, write-ups/demerits, performance appraisals, and the like.

Theory Y organizations operate on the assumption that most people seek meaningful work intrinsically and that they have the ability to solve problems in creative ways that do not require tight standardization. According to Theory Y, people can be trusted and should be treated as mature individuals, in contrast to the distrust inherent in Theory X.

Related to Theory Y, in terms of intrinsic motivation, Daniel Pink, the author of Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us [Pink 2011], suggests that three concepts are key: autonomy, mastery, and purpose. If these three qualities are experienced by individuals and teams, they will be more likely to feel motivated and collaborate more effectively.

Schneider and Westrum

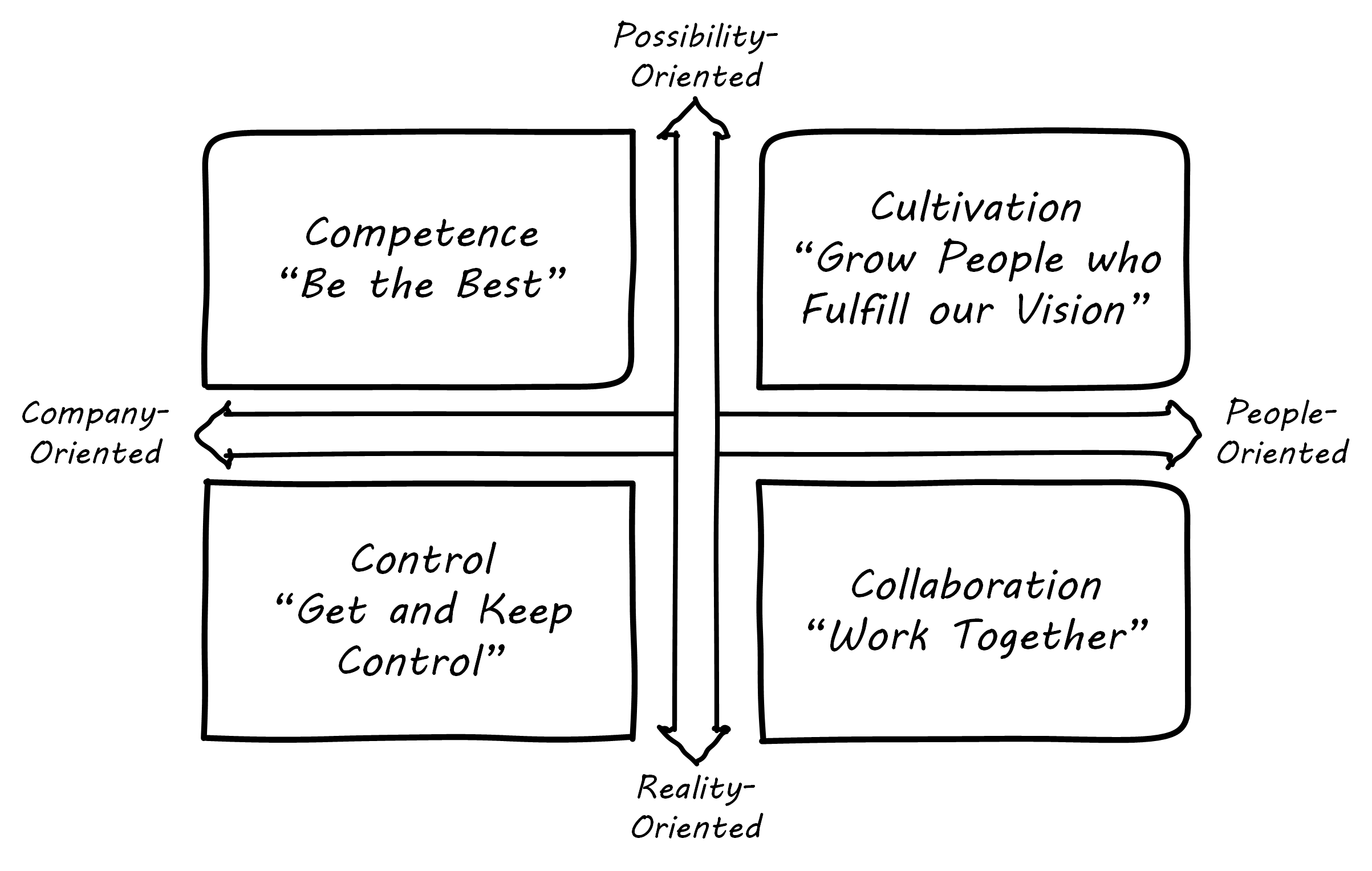

One model for understanding culture is the matrix proposed by William Schneider (see Schneider Matrix, similar to Schneider 2000).

Two dimensions are proposed:

-

The extent to which the culture is focused on the company or the individual

-

The extent to which the company is “possibility-oriented” versus “reality-oriented”

This is not a neutral matrix. It is not clear that highly controlling cultures are ever truly effective. Even in the military, which is generally assumed to be the ultimate “command and control” culture, there are notable case studies of increased performance when more empowering approaches were encouraged.

For example, military commanders realized as long ago as the Napoleonic wars that denying soldiers and commanders autonomy in the field was a good way to lose battles. Even in peacetime operations, forward-thinking military commanders continue to focus on “what, not how”.

In Turn the Ship Around: A True Story of Turning Followers into Leaders, Captain L. David Marquette discusses moving from a command-driven to an outcome-driven model, and the beneficial results it had on the USS Santa Fe [Marquet 2015]. Similar themes appear in Captain D. Michael Abrashoff’s It’s Your Ship: Management Techniques from the Best Damn Ship in the Navy [Abrashoff 2012].

Neither of these accounts is surprising when we consider the more sophisticated aspects of military doctrine. Don Reinertsen provides a rigorous overview in Chapter 9 of The Principles of Product Development Flow: Second Generation Lean Product Development [Reinertsen 2009]. In this discussion, he notes that the military has been experimenting with centralized versus decentralized control for centuries. Modern warfighting relies on autonomous, self-directed teams that may be out of touch with central command and required to improvise effectively to achieve the mission. Therefore, military orders are incomplete without a statement of “commander’s intent” – the ultimate outcome of the mission. Military leaders are also concerned with pathological “toxic command”, which is just as destructive in the military as anywhere else [Vergun 2015].

Similar to the Schneider matrix is the Westrum typology, which proposes that there are three major types of culture:

-

Pathological

-

Bureaucratic

-

Generative

The cultural types exhibit the behaviors shown in Westrum Typology [Puppet Labs 2015]:

| Pathological (Power-Oriented) | Bureaucratic (Rule-Oriented) | Generative (Performance-Oriented) |

|---|---|---|

Low cooperation |

Modest cooperation |

High cooperation |

Messengers (of bad news) shot |

Messengers neglected |

Messengers trained |

Failure is punished |

Failure leads to justice |

Failure leads to inquiry |

The State of DevOps research has demonstrated a correlation between generative cultures and digital business effectiveness (Puppet Labs 2015 and Brown et al. 2016). Notice also the relationship to blameless postmortems, discussed in Digital Operations.

Toyota Kata

Academics and consultants have been studying Toyota for many years. The performance and influence of the Japanese automaker are legendary, but it has been difficult to understand why. Much has been written about Toyota’s use of particular tools, such as Kanban bins and Andon boards. However, Toyota views these as ephemeral adaptations to the demands of its business.

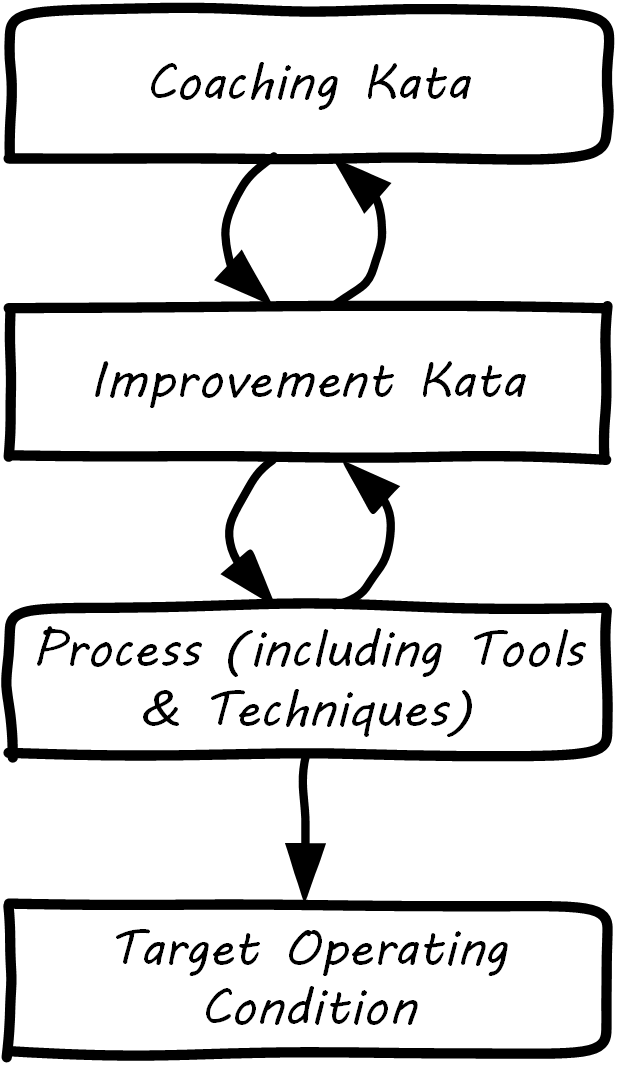

According to Mike Rother in Toyota Kata [Rother 2010], underlying Toyota’s particular tools and techniques are two powerful practices:

-

The improvement kata

-

The coaching kata

What is a kata? It is a Japanese word stemming from the martial arts, meaning pattern, routine, or drill. More deeply, it means “a way of keeping two things in alignment with each other”. The improvement kata is the repeated process by which Toyota managers investigate and resolve problems, in a hands-on, fact-based, and preconception-free manner, and improve processes towards a “target operating condition”. The coaching kata is how the improvement kata is instilled in new generations of Toyota managers; see Toyota Kata, similar to Rother 2010.

As Rother describes it, the coaching and improvement katas establish and reinforce a coherent culture or mental model of how goals are achieved and problems approached. It is understood that human judgment is not accurate or impartial. The method compensates with a teaching-by-example focus on seeking facts without preconceived notions, through direct, hands-on investigation and experimental approaches.

This is not something that can be formalized into a simple checklist or process; it requires many guided examples and applications before the approach becomes ingrained in the upcoming manager.

Evidence of Notability

Culture quickly emerged as one of the key concerns of the DevOps community. Google’s research into psychological safety is a concrete validation of its importance and notability.

Limitations

Culture is both intangible and a lagging indicator. Culture cannot be changed through exhortations to “be more collaborative” and so forth. However, organizational priorities that are perceived to be real – as in reinforced by performance objectives – can change culture. Work practices (including even the use of certain technologies) can and do change culture. (Skeptical? Think about how email changed work culture, for better and worse.)

Related Topics