Product Planning

Description

Product Roadmapping and Release Planning

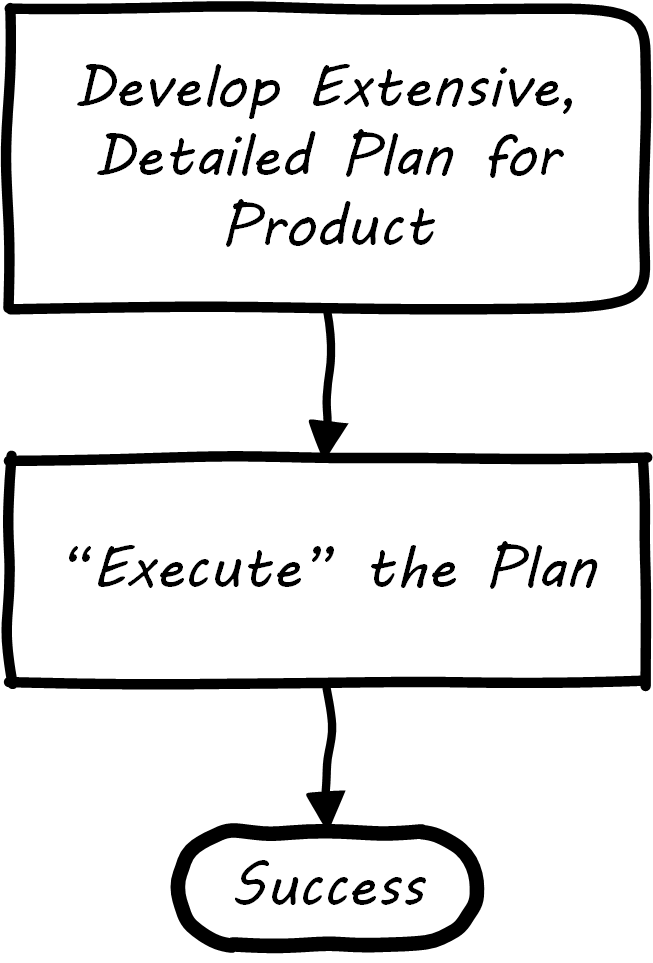

Creating effective plans in complex situations is challenging. Planning a new product is one of the most challenging endeavors, one in which failure is common. The historically failed approach (the “planning fallacy”) is to develop overly detailed (sometimes called “rigorous”) plans and then assume that achieving them is simply a matter of “correct execution”; see Planning Fallacy.

Contrast the planning fallacy with Lean Startup approaches, which emphasize the ongoing confirmation of product direction through experimentation. In complex efforts, the ongoing validation of assumptions and direction is essential, which is why overly plan-driven approaches are falling out of favor. However, some understanding of timeframes and mapping goals against the calendar is still important. Exactly how much effort to devote to such forecasting remains a controversial topic with DPM professionals, one we will return to throughout this document.

Minimally, a high-level product roadmap is usually called for: without at least this, it may be difficult to secure the needed investment to start product work. Roman Pichler recommends that the product roadmap contains [Pichler 2010]:

-

Major versions

-

Their projected launch dates

-

Target customers and needs

-

Top three to five features for each version

More detailed understanding is left to the product backlog, which is subject to ongoing “grooming”; that is, re-evaluation in light of feedback.

Backlog, Estimation, and Prioritization

The product discovery and roadmapping activity ultimately generates a more detailed view or list of the work to be done. As we previously mentioned, in Scrum and other Agile methods, this is often termed a backlog. Both Mike Cohn [Cohn 2009] and Roman Pichler [Pichler 2010] use the DEEP acronym to describe backlog qualities:

-

Detailed appropriately

-

Estimated

-

Emergent (feedback such as new or changed stories are readily accepted)

-

Prioritized

The backlog should receive ongoing “grooming” to support these qualities, which means several things:

-

Addition of new items

-

Re-prioritization of items

-

Elaboration (decomposition, estimation, and refinement)

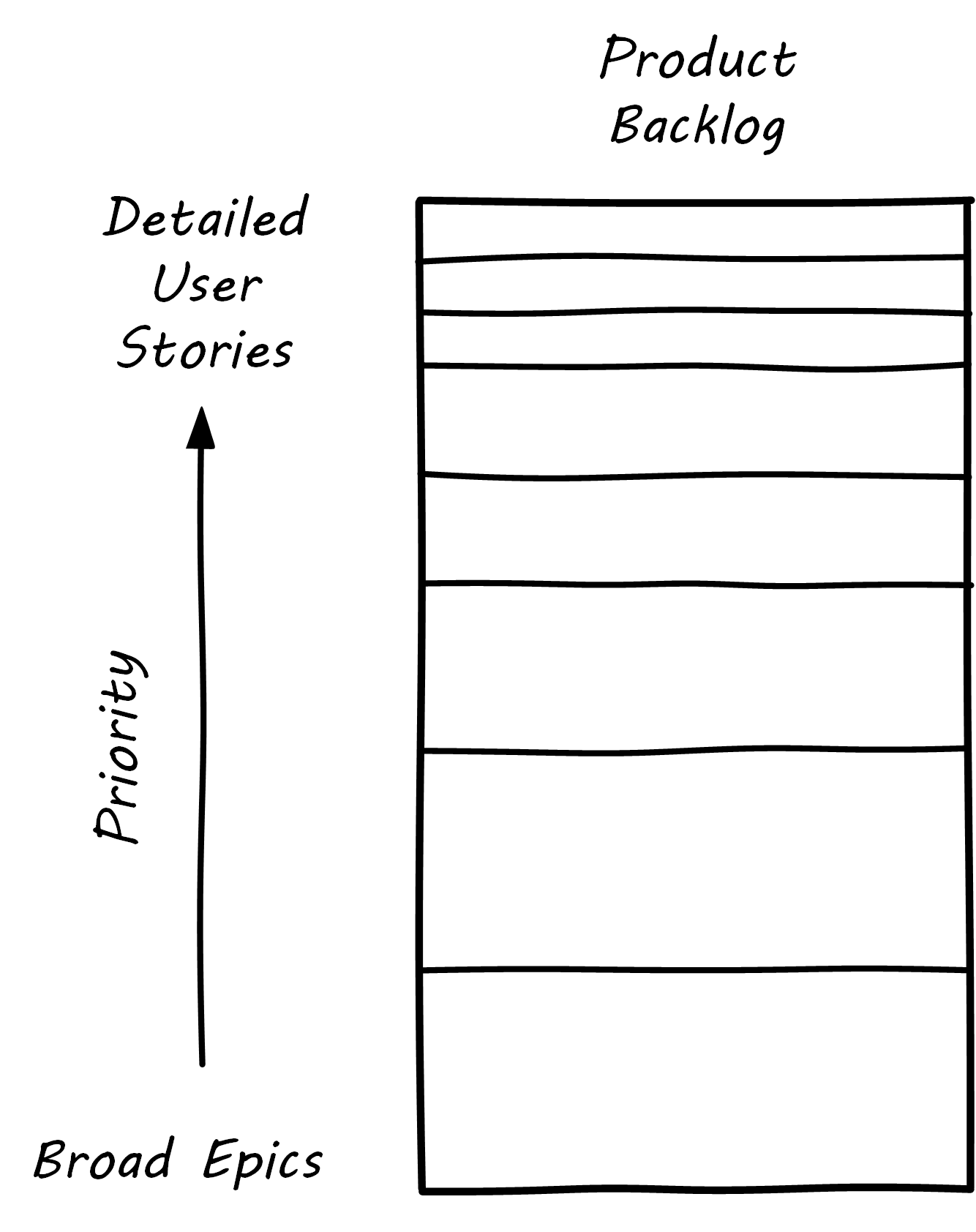

When “detailed appropriately”, items in the backlog are not all the same scale. Scrum and Agile thinkers generally agree on the core concept of "story”, but stories vary in size; see Backlog Granularity and Priority (similar to Pichler 2010), with the largest stories often termed “epics”. The backlog is ordered in terms of priority (what will be done next) but, critically, it is also understood that the lower-priority items, in general, can be larger-grained. In other words, if we visualize the backlog as a stack, with the highest priority on the top, the size of the stories increases as we go down. (Don Reinertsen terms this progressive specification; see Reinertsen 1997 for a detailed discussion.)

Estimating user stories is a standard practice in Scrum and Agile methods more generally. Agile approaches are wary of false precision and accept the fact that estimation is an uncertain practice at best. However, without some overall estimate or roadmap for when a product might be ready for use, it is unlikely that the investment will be made to create it. It is difficult to establish the economic value of developing a product feature at a particular time if you have no idea of the cost and/or effort involved to bring it to market.

At a more detailed level, it is common practice for product teams to estimate detailed stories using “points”. Mike Cohn emphasizes: “Estimate size, derive duration” [Cohn 2005]. Points are a relative form of estimation, valid within the boundary of one team. Story point estimating strives to avoid false precision, often restricting the team’s estimate of the effort to a modified Fibonacci sequence, or even T-shirt or dog sizes as shown in Agile Estimating Scales.

Mike Cohn emphasizes that estimates are best done by the teams performing the work. We will discuss the mechanics of maintaining backlogs in Work Management.

| Story point | T-Shirt | Dog |

|---|---|---|

1 |

XXS |

Chihauha |

2 |

XS |

Dachshund |

3 |

S |

Terrier |

5 |

M |

Border Collie |

8 |

L |

Bulldog |

13 |

XL |

Labrador Retriever |

20 |

XXL |

Mastiff |

40 |

XXXL |

Great Dane |

Backlogs require prioritization. In order to prioritize, we must have some kind of common understanding of what we are prioritizing for. Mike Cohn, in Agile Estimating and Planning [Cohn 2005] proposes that there are four major factors in understanding product value:

-

The financial value of having the features

-

The cost of developing and supporting the features

-

The value of the learning created by developing the features

-

The amount of risk reduced by developing the features

In Work Management we will discuss additional tools for managing and prioritizing work, and we will return to the topic of estimation in Investment and Portfolio.

Evidence of Notability

Product roadmaps are one of the first steps towards investment management and strategic planning. There are robust debates around estimation and planning in the Agile community.

Limitations

Roadmaps are uncertain at best. They are prone to false precision and the planning fallacy.

Related Topics